Initially everything seems familiar, as if it has been seen many times and left behind, stepped and passed, or it is even better to be passed. Vague and clear associations and parallels appear - with other times - with other films, their other content, in them - with other people and their adventures, their problems. with other parts of their/others' lives, other developments and other (and/or similar) endings.

However, this similarity or the feeling of familiarity soon disappears. Immediately, when the way of narration acquires a new color and load; when the shots are filled with air and space, with artistic prints and clear and bright backgrounds; when the shooting points or perspectives move to non-banal and timeless dimensions; when the quality of the image changes, the action becomes emphatically mobile and dynamic, and it falls into the realm of the gaze, free from dogmas; when the direct attitude and position of the director begins to emerge and the bold and free transformation of "traditional" cinema forms, “habits and customs" begins.

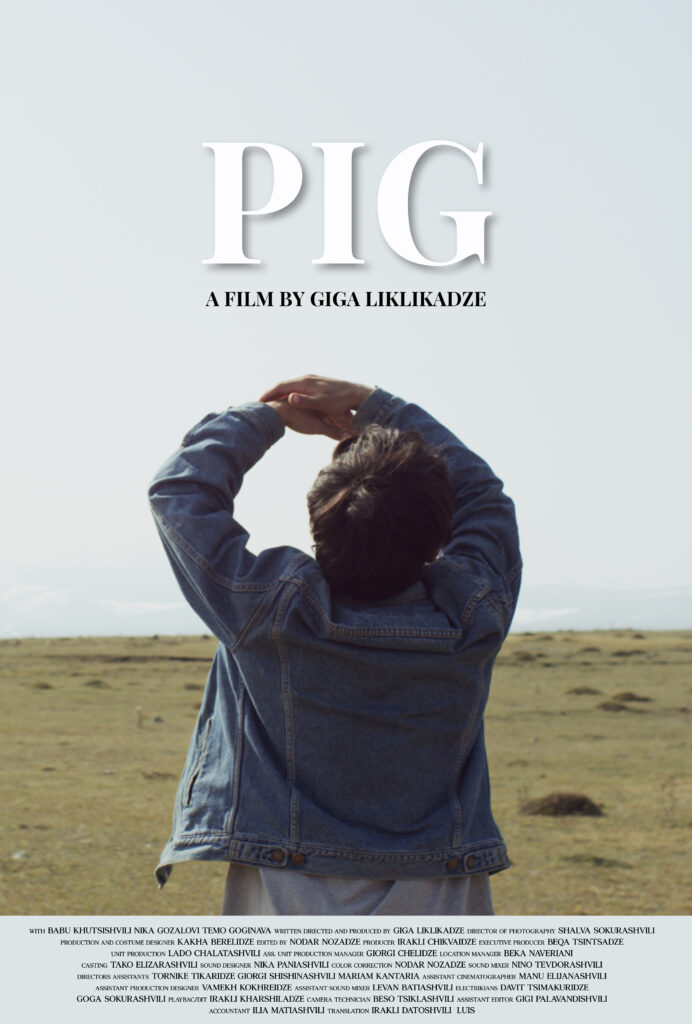

Giga Liklikadze's film "Pig" (2019), is one of the outstanding, original and controversial films of the new Georgian cinema filmed shortly, concretely and ironically, with his own script, which provides the basis for free perception, attitude, reading, creating a portrait of the modern society, where we live and represent. Irony, parody and disguised support and sympathy are the main techniques and tools for flexible management of events. The story, at first glance, revolves around an invisible pig, and this word clearly expresses both the essence and the problem of the film. It is perceived as an articulate metaphor. Only three visible characters and the rest with off-screen ones and a "simple" plot scheme.

The story develops as a criminal drama, which, like everything else, loses its genre intensity and turns into a psychological drama, captured in an acute, but ironic, artistic form of the spiritual crisis of society.

The action areas of the film are also "familiar." Either Tbilisi, or Zestafoni, or Samtredia, or Kaspi, or Rustavi... or, or... in short, West or East, maybe even South... Georgia. The nature of Kartli and Imereti resembles biblical landscapes. Endless and trackless fields, valleys, hills, prickly hedges. Suburbs of deserted cities, ugly streets without recognizable signs, or highways passing through villages and towns... wretched shops, cafes and wine and beer cabins, crossing or river bridges, scrap railroad tracks, churches, bus stations, factory pipes, middle-class and "aged" cars, middle-class and socially vulnerable and antisocial types, young people, maybe even teenagers, or a little older.

At the beginning, a passenger bus is going somewhere. A "familiar" trip (to the village, to oneself or somewhere else), to run away or to be forced to return home when you have no other way and nowhere to go. Then the bus breaks down. In a wide open field or on a hillock with dug dens, people get off the fatally damaged bus. First, everything is not clearly visible from behind the windshield, and that's why the sounds are heard, quite deaf and slightly muffled. There is silence here and later on. Only the chirping of birds, other sounds of the river and nature, the voices of people are heard. Then such torpidity is rarely interrupted by a phone call, which often does not "connect" or is disconnected, due to non-payment or because it is not answered. This is also such a sign of times and circumstances. There is no music in the film either. Not time for music. Or what’s music got to do here!

One is separated from the passengers and continues to travel alone - 20-year-old Bachana (Babu Khutsishvili), defective for the army, helpless, weak and homeless. He is, as it were, led by fate to this desolate place to pay himself what will be paid, and thus the main line and conflict of the film begins, closes, opens and ends. Only he goes in the other direction, rolling the bottle he found in the field. There is a pale autumn sun, the grass is withered, and here and there blackberries remain on the bushes. The wayfarer eats berries (as if closeness and unity with nature) and gets lost in the bramble thicket. In these ravines, two young people Makho and Ramo (Temo Goginava and Nika Gozalov) dressed in "standard" clothes of specific texture and manners, lost in life and also homeless, run into him, pester him, kidnap him and demand a ransom from his family, "just" 300 Lari. The family does not have this amount, and the kidnappers need it very much because neither they nor many others have - 300 (or 200 Lari). At this time, the figure of a pig "appears" - on the one hand, as a ransom, on the other - a mythical creature, or a hallucination (Bachana's dream), and what’s more, an object of the author's irony, which no one can see anywhere. And neither will/can sell.

Actors (only Temo Goginava is a professional) behave and speak as those who they portray actually behave, act and speak. They don't seem to care what's going on around them; whether someone is watching or listening, just like in real life. They are free and open. Without complexes. Natural ones. And reality comes from all angles and nooks and crannies. The screen reflects reality. No matter how unbelievable the story is, Bachana and then Makho and Ramo, already the main characters, will befall.

Bachana leaves and cameraman Shalva Sokurashvili's "hand" camera follows him. With "jumps," uneven and rough movement, choppy, hacked and "irregular" motions, "trembling," where the lens "runs away" and what gets into the eye. As events change, so does the style of photography takes a new direction. But it is never calm and balanced. It won't be, such stories hold sway. Everything changes when the scene of action changes.

The action moves from open space to an old, seemingly abandoned house, in which robbers live. A microcosm, or a micromodel of life. In strangely bolted dimensions, in an empty or completely deserted village. Here, the kidnappers are holding a handcuffed boy and live a normal life. They smoke, waste time in idle conversations, play cards and wait. With weak hope and strongly expressed aggression. Here, too, familiar signs of kidnapping, home as a refuge and a metaphor covering the past can be seen from other Georgian films. But this distant association soon fades like all other associations. The "pig" house stores other memories and information and is a different, expressive way of life of others, in the form, content and interior, collected with old things (production designer Kakha Berelidze).

"Black" slang, profanity, swearing, as a characteristic of thinking, mental abilities, mental closure and primitive limitation of speech, spoken topics. Swearing - as contempt and aggression, hatred - as a sign of time and the cause and effect of everything. The point is that "this" and "such" people speak only such language - are they angry, hurt, happy or indifferent. However, there is no one who is indifferent, calm and hopeful here and never will be. Very familiar people from the real environment, their way of life and form and their banal logic. In the film, it is even more exaggerated, intensified, even grotesque. This and, in general, a parody of other movie stereotypes. Both ironic citation and violation. Criminals are also unmasked when a single call from the grandmother (that no one knows who this dangerous grandmother is!) can scare criminals and stop them from committing a crime.

Both Bachana and the kidnappers have their own personal fears and hopelessness. Usually, they belong to people without a reason and no future, who are not lucky in anything. A spectrum of problems of "out of place" and monotonous daily, social, mental and communication problems of young people "lost" in time and space is created. Rarely (or not at all) is an "internal" portrait of a supporting society drawn. Surrounded by the panorama of today's Georgia.

“I mean how do you know what you're going to do till you do it? The answer is, you don't. I think I am, but how do I know? I swear it's a stupid question", so does Holden Caulfield, the hero of Jerome Salinger's cult novel "The Catcher in the Rye" (published in its entirety in 1951 and, by the way, on July 16) conclude his narration conclude his narration, one who represents the "angry" youth of the era, he became a symbol of their worries, misplacedness, roadlessness, fears, loneliness, solitude, dissatisfaction and their own protest movement, rebellion. Of a generation that was not lucky. And who yet defeated reality.

The heroes of Giga Liklikadze's film are also modern young people from a generation that was not lucky. But they haven't revolted yet. Bachana knows "exactly" what he doesn't want, but he also knows exactly what he will do and how he will live, because he has no choice about what he will do or how he will live. No one asks stupid questions either because no one cares to hear the answer to them.

In film, nothing is beautified, plastered or polished. It is as it happened, is happening and will happen. This world seems to sway slightly with the gentle blowing of the wind. While the director looks directly at the object, place, event, story, time; when he connects the shots with each other in his own way (editing by Nodar Nozadze); when beyond social, public, or even political influences and compulsions, there is a refusal to pay tribute, there is a price for pain, and there is a great power of resistance.

As pathetic as it may sound, it is wonderful when you see that a person, an artist, is free. He is free from dogmas, "imposed" or self-imposed norms; he is free from frameworks, system captivity; from big budget and other canonical ambitions; he is free, no matter how reality should be bound, and no matter how strong stereotypes the society has, the sameness of sensation-perception of reality and "cinematic rules." It is wonderful when an artist can overcome the depressing influence of reality, avoid it and step beyond the framework, go through a closed door and leave it open for someone else. To try and do what he believes in, because he wants to change something, because he knows that getting rid of barriers, even on the road, is still possible by taking steps. Only then is it possible to surpass reality. Unlike Bachana, Makho and Ramo, Giga Liklikadze and the directors of the new generation behave exactly like this.

Lela Ochiauri

IF YOU OVERPOWER REALITY