Is there such an interpretation of disagreements between generations in Georgian art, in particular, dramaturgy, cinema, as Gertrude Stein's search for the explanation of the creative realities and psychotypes of the "lost generation"? This is still controversial and will probably take decades but it is clear that more than (or already) 30 years have passed since the collapse of the Soviet system and the somewhat illusory vision of the "lost generation" is still important for cinema, theater, literature. In the end, there is nothing negative about this either - the pain, loneliness, tragedy, drama of any generation carries with it its illusory phantoms and stereotypical fears: mostly exaggerated or underestimated. For cinema, and for one with such important historical transitions as Georgian cinema, this is also a common occurrence. From the point of view of artistic development and in this thematic interest, it is less expressive how everyday existence is drawn for the most part, what remains stereotyped in it and what starts the process of a new vision.

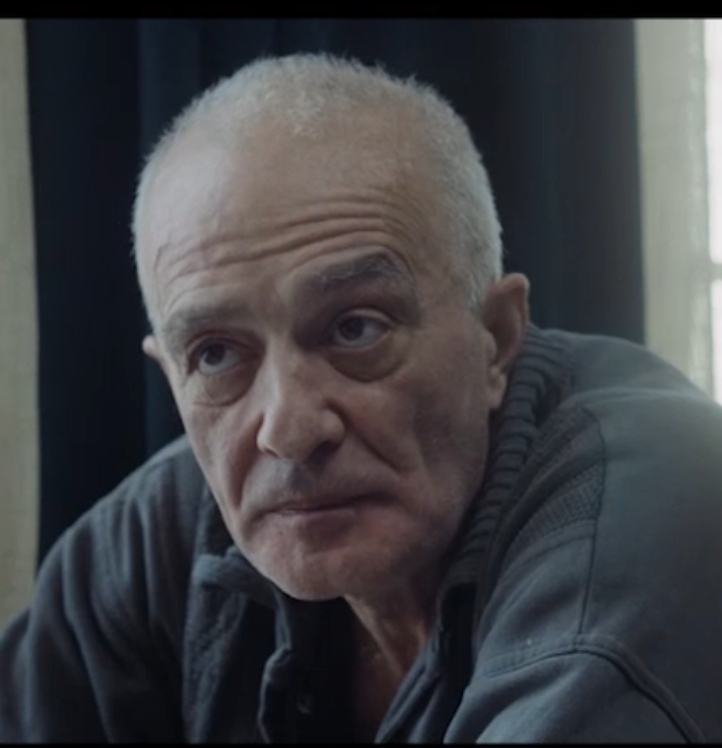

Ilo Ghlonti's film, "Why Are We Together" (2022), is the story of a family with several generations, of life and history of Tbilisi: a 20-year-old boy, Gio (Ivane Ghlonti), who lives with his father (Levan Ghlonti), is accused of robbery by the law enforcement officers, and it costs uproar to all three generations of the family, grandparents (Marina Kubaneishvili, Tamaz Abesadze) and uncle (Ilia Ghlonti) in the process of finding the ways of his release, as well as his father's temporary imprisonment and the search for "another way" to set his father free. In the early work of the same director, the importance of dramatic family existence appeared in the film "Five Variations," which the director shot in 2005, the main thing - the inevitable, dramatic necessity of being together was presented even then as an interpretation of the main essence of existence. Grandmother, grandfather, uncle, father, son, father's friends, and so on endlessly seem to be in the unified perception of existence while discovering, highlighting, and calling the main thing in the relations of this circle. While describing this simple philosophical concept of existence - the profound meaning of being together, the authors of the film script (Ilia Glonti, Levan Glonti, Archil Kikodze), the film director and cameraman (Mindia Esadze), choose simplified, non-pathos-created images of existence rather than demonstrating a dramatized feeling.

This is a subtle and good position but it is still a relevant sign of Georgian cinema of the 21st century, which mostly still follows the history of the 1990s: in all those episodes where one of the most important and interesting character, the grandmother (Marina, as she is addressed) has to express her own attitude towards modern reality, her calm, non-irritating, intonation-correctly directed long lines still acquire an overly emphatic look and sometimes fall out of the unified, correct compositional reality. Such is the episode of conducting the apartment search, the elderly woman's righteous but frustrated indignation and even one glance at this vulnerable character in the shot is enough to make most of the phrases she utters seem completely superfluous. Another question is how organic this text is in the dramaturgical fabric - after all, it is a continuation from the beginning to the end of the natural reaction of the elderly heroine to injustice. Therefore, not the monologue itself divided into half-replies about the loss of dignity, but these uttered phrases in this specific and several other episodes will not be felt as a natural expression of a completely justified and well-made reaction.

This environment created by the film director and scriptwriters is both familiar, nostalgically sad and simple in its meaning. It is true that associations are easily born with the examples of the details of being on the screen, which are abundant in Georgian cinema since the 1990s, but this does not mean anything, especially since any socially familiar space always contains identical signs. The main thing is how interesting this or that aspect of its artistic interpretation is. Whenever an interior depicting the heroes’ presence appears in a Georgian film, the expressive details of authenticity (if authenticity is a priority feature) are less noticeable. Or rather, less pronounced. This special feature is repeated by the main interiors of the film - as a constituent of the character of the time and the person. The environment, as a kind of quotation of time, can be essentially no different from what we touch in everyday life. It is possible that we may not feel the details of the similarities at all - it all depends on the general sign of the mood, although the common and associative in this film are more than distinctive and different.

If we think about a distinctive and different motive, then perhaps it should be said about the simplicity of relationships and something characteristic of intergenerational attitudes, the silent, almost wordless expression of avoidance and respect, whether it is the English lesson that Marina is giving to her granddaughter or the discussion of the meal prepared for breakfast silently, the attitudes stick to each other without words.

It is strange when there is nothing new in these relationships and at the same time, what is always important is overlooked - heartbreak over the past, regret. It is as if the desire to exist anew does not even exist - at least such a feeling really arises until it is replaced by another, no less interesting feeling - is it less vital for the less human or personal fulfillment of the past and the generations that come from the past to be together? Or who imposed on humans the duty of abnormal pursuit of permanent changes in the environment? These relationships, brought by simple feelings, do not bind the heroes of the film with the past and do not oblige anything regarding the future because it is natural for them to be together. It's as natural as knowing each other's strengths and weaknesses.

Since the 1990s, social reality has clearly dictated its own conditions to artistic processes, although the process has always taken a heterogeneous form and, in most cases, ended up with a distorted narrative. Perhaps, that is why any true story, which is artistically interpreted in modern Georgian cinema, should be doubly interesting. The authors of the film manage to reject this artistic expression. It really takes some time to interpret naturalness and establish it as the norm. Ilo Ghlonti's film is one of the examples of the result of this long process, which, along with self-realized values also tries to clearly present the main signs of character. The calmness of Temo's character and the slightest impulsive reaction coexist with the philosophical wisdom of the older generation and a poor understanding of the violent world.

After the 1990s, the experience of decades made these heroes and their authors find another way: the difference in the opinion of "being together" also revolves around one thing - the real need, the whole continuous chain of relationships is in such simple actions, which are sometimes only under one roof, for one reason to have breakfast. It can mean being together and silent around an ordeal or during one laboratory study, in cold weather...The tragedy of the "lost generation," apart from war and social catastrophe, always and everywhere was hidden in the deficit of the philosophical necessity of being together.

Ketevan Trapaidze