One of the biggest strangeness of the modern world existance, which at the same time is difficult to accept, is a tolerant-minded society which is obsessed with the complex but can do nothing to adapt to the inevitable truths of life.

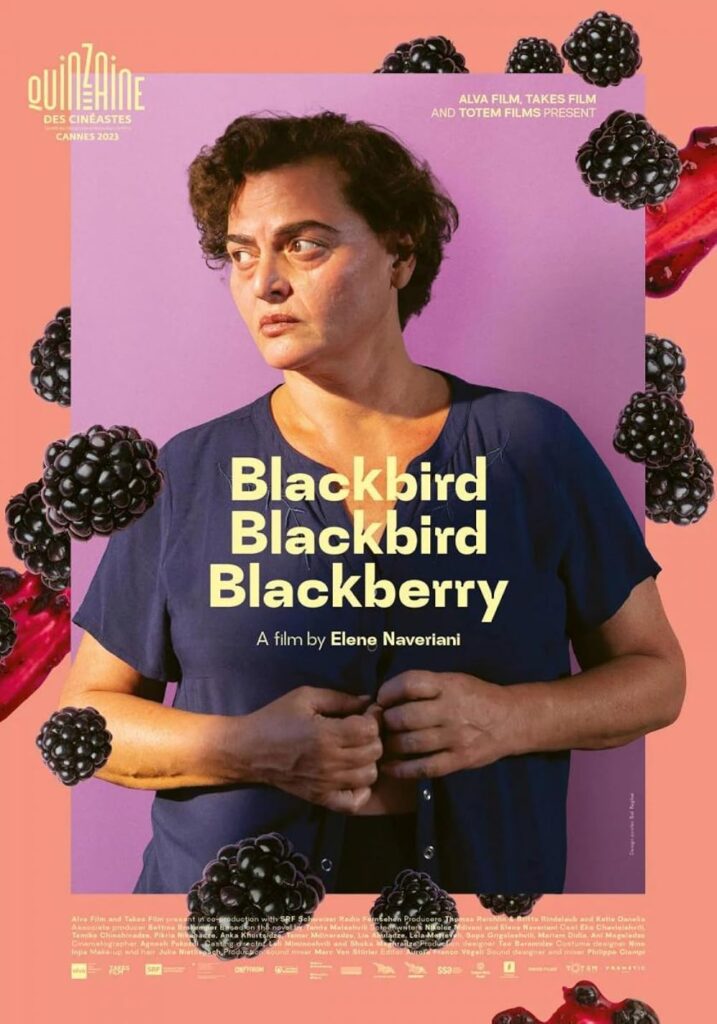

The film "Blackbird Blackbird Blackberry” (2023, dir. Elene Naveriani) is a screen adaptation of the story of the same name. In general, depending on the tradition of screen adaptation, the audience looks for a "new vision" or subtexts read by the director. Tamta Melashvili's story about a middle-aged lonely woman, Etero, working in a shop, includes the life of a person lost in forbearing rumors of a small settlement (town, village) and an accidental romance. The fear of death, the decisions made in the face of imminent danger, an unexpected pregnancy at the age of 48 – all this is formed into a dramatically intense plot, in a certain type of characteristic literary narrative. The main character of the film (Eka Chavleishvili) does create a character built on the framework of the interpretation of the literary primary source, which brings different, radically naturalistic signs of aestheticization to the audience.

Etero and her accidental hero (Temiko Chichinadze) offer us an intense, naked moving chronicle of their own desires in a frame where the story itself is clear. In turn, the environment, the space in which these two heroes live, is completely grotesque and far from reality and where it seems that everything is presented in a deliberate scheme - either "good" or "very bad." It is exactly like in the social realist "good" and "bad" or "good" and "more good, bettering" society. Neighbors, women of different ages, immersed in an insatiable desire to gossip and ridicule, try with such maximalism to loudly and openly display their episodes of disgust or aggression that it is not even clear whether we should accept a grotesque part from these characters or simply excessive pathos is to blame for their false manners. The more specific and restrained the main character's scanty clothes, behavior (in several episodes), the more comical the caricatural circle of neighbors is, who are excited about the topic of unimaginable colorfulness and sex.

If the claim (and it is clear that such a position exists) is based on an organic combination of the realistic and the conditional, then next to Etero’s character, such an unnatural variety of neighbors-friends is simply an outrageous addition of a set type, which cannot be found in any category of reality. At this time, any verbal justification of "murderous public opinion" would not be interesting, since such a society does not cry out anything new, its existence is not new to be noticed, nor is such an unnatural grotesque of women's society even remotely close to the sentiment, whose sad directness is displayed with keen intuition of Eka Chavleishvili's Etero.

Any contrasts that are part of Elene Naveriani's peculiarly minimalist aesthetic on screen in describing heterosexuality are often rendered meaningless when that existence collides with an apparently hostile and aggressive environment: the process of aimlessly pedaling sex with hidden and never-ending accents, whether it's a party with the women next door or a trip to the city with a well-disposed pair of young girls, where everything is good, since this couple doesn't fit into the "traditional" format of the relationship either (accordingly, they, "better than good" characters, radiate only goodness).

The contrast between the real and the imaginary can easily turn into a self-serving contradiction. The multi-colored cake on the porch of the house is too comical, as is the dancing lady and another representative of this circle who talks about sex with aggressive cynicism and gesticulation. This episode is neither satirical, nor grotesque, and it contradicts what the behavior of Etero’s character, who is often surrounded by purple lights and shadows, tries to consistently assert: she has the right to exist in a micro-space of freedom and peace. Despite the fact that Eka Chavleishvili’s work itself really arouses interest in this regard and, due to the fact of a number of restrained assessments, the scheme of its artistic characterization still follows a very simple, naturalistic logic, it cannot be mistaken and asks questions: the episode about an imaginary tragic death is interesting, dramaturgically and artistically sharp. Its compositionally full setup (meaning this episode) is intense. Instead, this fear, primal and evil instinct, well and dynamically moving, in this very episode seems to die, with its interesting aesthetics, and its place is taken by a fake image of a conventionally insignificant and unexpressive world. This is the main artistic inconsistency, which makes us lose the feeling of a unified artistic fabric, and the second, no less grotesque, are the details in the nakedness of the main character - those nuances brought forward during bathing, at rest or when a woman wakes up, which do not say anything in particular, nor do they add anything concrete to her general mood except for one - as if on the desire to establish less interesting aesthetics. This desire itself would be natural, if not for a simple question: does all this leave a natural feeling of artistic fullness and interest?

The desire to oppose the existing norms of being or even the norms of being intensified by the imagination does not yet mean the desire to oppose all events and ways of life, where the non-conformity is not the thought, but the distorted, less interesting form of the embodiment of the thought. The tried-and-true aesthetics, presented many times in artistic trends or author cinema, brought to the point of naturalism, are justified if they are considered in an artistically full conceptual way.

The first thing that is naturally heard and born in relation to a film or a work is freedom, the completely natural and the only natural motive, which is the main thing in the dramaturgical-artistic beginning of a film. It is another matter to what extent this spontaneity of heroes who are interested in freedom or becoming freedom is visible. Neither boldness (which, of course, should be noted), nor artistic interpretation of any topic, even a taboo one, can become a problem, and no one disputes this. It is debatable to oneself and in the process of perception, how naturally and how interestingly the topic is interpreted.

Etero’s or any other character’s life cannot be tragic or, on the contrary, full of happiness just because being full of other attitudes and longing for freedom, she does not recognize any stereotype of life. Both the problem and the unacceptability are in her fears – which, by the way, caused the most interest and unfortunately could not be developed as a motive, as an artistic dynamic of behavior and events.

To the eternally relevant question, is there anything that "can't" be shown on the screen, the eternally simple answer "awakens" too: showing, imagining, expressing, everything is possible! It depends on who does it, why and how.

Ketevan Trapaidze