It is difficult to distinguish a film in works of genius directors and say that one is better than the other and can be called a “Magnum Opus.” No matter how often you watch the best directors’ films and you may especially love some of them but you “admit” that they are all masterpieces in their own way. There are no great directors in whose work there has not been at least one film that you think is far inferior to their talent and ability but this has not diminished their glory in any way despite the fact that they have been widely criticized by film critics and have not missed the audience’s attention. Francis Coppola, Steven Spielberg, Werner Herzog and many others are included in the number of these directors. Later, when Federico Fellini made the film “City of Women,” it turned out to be dramaturgically incomprehensible and thematically chaotic. The film was so weak that it was even perceived as a caricature of his style. We Georgians have many such influential and talented directors, and one of them is Merab Kokochashvili.

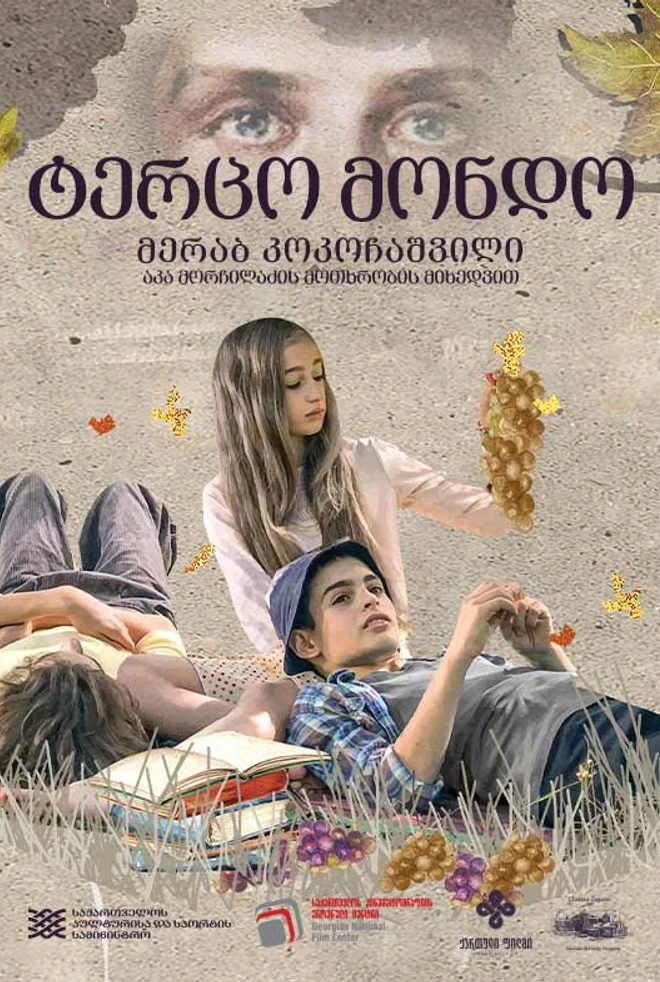

“Terzo Mondo” (2024) is the name of Merab Kokochashvili’s new film, which he made after a long pause, at an age when people are as sincere, delicate and honest as children. It is precisely such childlike sincerity and honesty that the director shows in his film towards the issues that worry, hurt and make him think. Although the film lacks a clear dramaturgical development, perfect performance technique, and in-depth mise-en-scène, one can still feel the emotion and feeling while watching it that great artist thought especially carefully while working on each episode and approached such a painful topic that has become an incurable pain for Georgians.

The film tells the story of two mates whose relationship begins at school (during the Soviet period) and continues into adulthood. The conflict in their relationship flares up in childhood because of their love for their classmate Natia, and in the 1990s, when the civil war was raging in the country, it becomes more intense and they even become enemies of each other because of their different political views. As adults, many years later, they meet again, now in a foreign country, where the bittersweet memories of their childhood bring them together again. The conflict, which began in their childhood, does not give them peace, new misunderstandings are added to this and the relationship between them is once again strained.

These eras, generations and stories: the civil war, childhood in the village, the love of two mates Aka (Levan Tsuladze) and Mojito (Duta Skhirtladze) to one girl, the agreement in the president's bunker, the character happens to get this whole story written by the main character, are dramaturgically tangled and mixed together in such a way that it causes narrative and stylistic chaos. The dialogues between Aka and Mojito are so fake, artificial and theatrical that the cinematic language is lost somewhere. Despite the fact that the cameramen’s (Davit Gujabidze, Giorgi Kharebava) work is quite meaningful and profound, it is still not possible to "cover up" the chaotic dramaturgy of the film, the unnatural timbre of the actors' voices, gestures and facial expressions. By focusing on details, the camera tries to make the story closer to the viewer and evoke the feelings and pain that the civil war of the last century had a profound effect on the psyche of Georgians, tearing them apart and creating a huge gap between them. Not only does the cameraman's eye record facts and events but also tells the story in a way that enriches the director's idea with in-depth perspectives. The composition of the shot is sometimes distinguished by poetry and special sensitivity to details, which creates an emotional atmosphere. Static shots emphasize the characters' feelings frozen in the past, which are transferred to the present.

At the beginning of the film, against the background of the credits, the cameraman takes a slow panoramic shot of a night street, where fire-breathing bullets move at lightning speed in a populated area. The camera moves into the room and begins a detailed description of the interior in a continuous movement, allowing the viewer to feel the space not only physically but also to create an effect of tension and anticipation. The slow movement of the camera creates a sense of time and space that has a hypnotic effect on the viewer, and reaches a tense, deep and emotionally overwhelming climax when a bullet fired from the street penetrates Natia’s heart, who is leaning against the window. This shocking scene, which has an effect on the viewer from the very first shots, is quickly nullified by the following scenes.

The meeting of the friends who have not seen each other for many years in a foreign country leaves an overly theatrical feeling, which is so far from cinema that their acting seems more like mockery than revealing the characters' nature. The unnecessary dialogues and lines in the film sound completely out of context. Aka Morchiladze's story, "Terzo Mondo", on which this film is based, is almost entirely built on dialogues but these impromptu phrases and words follow each other as freely and consistently as pearls strung on a thread.

Keti Shatirishvili, unlike the rest of the actors, authentically conveys the character’s emotional state. Her dance in one of the episodes of the film is not just a graceful movement of her own body, but it is the swaying of her inner free, or more specifically, «Basque roots», which expresses the longing for freedom, the freedom that we Georgians lack so much. And, if we take into account the opinion of some scholars that the Basques are related people to the Georgians, we can even perceive their dance as a symbolic metaphor for the Georgians' desire for freedom.

The term “Terzo Mondo” often refers to underdeveloped countries and here we most likely refer to Georgians (and not only Georgians). It is also symbolically associated with the heroes’s conflict who still could not completely forgive each other for their childhood mistakes. “Terzo Mondo” is also perceived as the internal confrontation and conflict of relations that we endured in the previous century. Now it is the 21st century and we are still going around in circles, again in conflict and head-butting each other.

What is this film about in general - about the civil war? About the hostility of Georgians towards each other? About the “love triangle”? About the attitude of Georgians towards European transsexuals? About free sexual relations? About the friendly attitude of Armenians and Turks in Europe? What is good about Europe with its equality and carefreeness or what is bad about Europe where depravity and love are mixed together? And if about everything? The film might mostly be about everything, and even more so about Georgians, who could not completely wash away the feces that appear repeatedly in the film. The director wanted to say a lot about what hurt him, what he experienced, what he thought and worried about, but in the end he could not fit it all neatly and beautifully into the running time of one ordinary film. Added to this was the fact that shooting of the film coincided with the Corona period, which slowed down the filming process and took years to complete. This time gap is reflected in the film's editing and dramaturgy, during which the conceptual connection between the shots is often broken and the topic suddenly changes so that the emotional connection between the film and the viewer is abruptly severed.

The most important thing might be the fact that Aka and Mojito are just as sad about the “handlocked" Georgia as the director himself, who tried his best to convey this heartache. He thinks not only about the fate of Georgia but also about the tolerant, loyal and friendly relations between different nations towards each other. In the episode of the pool, where Turks, Armenians and Georgians meet, Aka admires the cooperation between Armenians and Turks. Their performance of Beethoven's 9th Symphony perfectly expresses the essence of Friedrich Schiller's poem "Ode to Joy," while Beethoven's pathetic melodies perfectly blend with the characters’ passionate mood, sending a direct message about humanity, unity, and freedom.

The film unfolds entirely in flashbacks, reflecting Aka's own inner anxiety and feelings. Although many years have passed since the heavy, bloody civil war, as well as the painful incident when his girlfriend in the apartment was killed by a bullet fired from the street, neither time nor the busy life of Europe has dulled this pain, but on the contrary, meeting his friend has renewed old wounds and made him lose his peace. The friends’ love story experienced in childhood takes on a new form in adulthood, and the director reunites them around one woman. The director seems to be trying to use this "triangle" to return them to their childhood in a new form, with different feelings, with more European freedom, which ultimately gives their relationship and friendship an indecent hue and causes disagreement.

Although much in the film is artificial and unnatural, one can feel the great humanity that the desire for friendship between different nationalities generates. Everyone has their own traditions, culture and views. Georgian, Armenian, Turkish, Croatian, Abkhazian, Greek - all those who appear in the film create one great warmth and love for each other. The director's main goal might have been to unite everyone, make friends and tell the audience that we will all sing the "Ode to Joy" together sooner or later despite having different cultures, traditions, temperaments, being on the right-wing or left-wing.

Ketevan Ghonghadze