Studying chess not as a sport but as an indicator of intellectual resources that exist in itself is one direction, but the quest for people’s personal portraits associated with it as well as the history of our country's transformation into a chess phenomenon is another direction in today's world. Today, we face and perceive a reality from all sides, where the saying "the smash of authorities" is declared a primitive goal in itself.

In the country that has turned into a chess phenomenon, where women have held the world championship in professional chess for decades, no one is surprised today how people struggling with misfortune use these names as a target for their own aggression or insults. This is part of the primitive everyday life of modernity - after all, there is a history that never reminds us how many failed poets and writers trampled on the name of Galaktion Tabidze or any other creator, since the identities of the offenders simply disappeared over time, like gray water naturally mixed with rain. This poetic digression might also be justified if we recall how many times this eternal disease existing in modern reality has tried to strip the most important figures of Georgian history of their true dignity at the cost of covering up their own insignificance. And as this fact acquires sharper contours, as the genuine reasons for this insignificance become clearer, any step in documentary filmmaking aimed at immortalizing history arouses more interest.

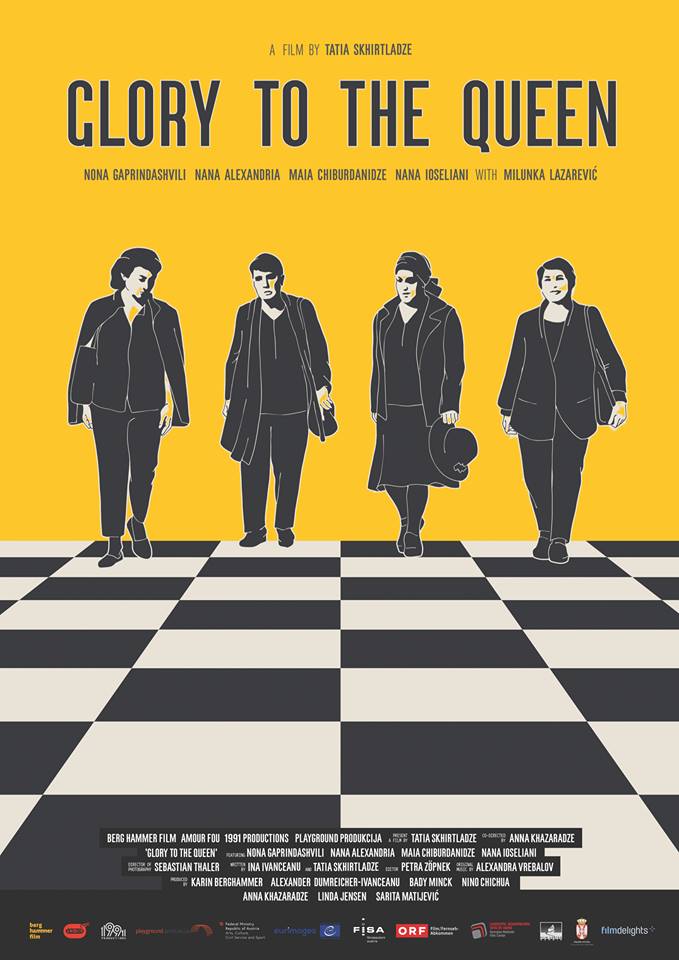

Tatia Skhirtladze’s full-length documentary, “Glory to the Queen” was shot in 2020 and creates several personal-artistic documentary portraits of Georgian chess queens, and by the decision of the Georgian director living in Austria, its entirety is woven into several stages by the narrative of Milunka Lazarević, a champion and theorist of the Yugoslavia (as the country was called before its collapse) period, as if into partitions and parts divided into each of their biography. These parts are valuable in themselves, have become chronicles with their authenticity, are built on the personal artistic vision of these four and are distinguished by the direct attitude of the author.

The chess adventures of Nana Alexandria, Nona Gaprindashvili, Maia Chiburdanidze and Nana Ioseliani should be intertwined with their personal character portraits (at least, that's how it reads).

Interviews, the unmistakable and one of the most interesting methods of documentary film, are quite difficult to fully reveal these women’s characters, even if the goal was only a descriptive record. The interviews with Nana Alexandria and Nana Ioseliani are distinguished by a clearly pleasant, slightly limited scope of action not in every episode, but often. I mean the feeling that in the episodes of their walking, visiting different places, their lives, as if in a fragmentary narrative, is based only on the momentary mood, and not on understanding these portraits as a whole. It is possible to attribute this to the plot, to the character of these heroines themselves, which evokes a slightly indifferent mood, although this does not apply to either the environment or the reality in which they live and work.

Being chess champions, with their traditions, failures and struggles, was part of the reality of the Soviet country for these four heroines. The documentary archival material, which the author presumably obtained from the TV archive, creates an incomplete but very interesting idea of the era in general, although I find it somewhat forced to emphasize off-screen how, for example, Nona Gaprindashvili's family was forceful to sit or behave in exactly the way the ideological framework dictated to the authors of the report. The point is that the documentary nature of television reports of the 1970s was not entirely distinct from what was established by world television culture. This is the general need for visual and behavioral norms in the characteristics of that era. This is neither new, nor the truth discovered today. For example, in order to present American actors’ existence with special intensity, the journalism of that era sought a balance in both appearance and behavior and only began to search for a connection with naturalness when it found something negative. Naturally, the ideology of the Soviet country had its unwavering demand for the preservation of signs of external well-being, although the extent to which all this was only a feature of our television documentary and reportage genre is debatable.

This is only one side of the reality in which Tatia Skhirtladze creates Nona Gaprindashvili’s portrait. In other cases, she shows a very interesting personal "I" - calm, thoughtful, occasionally full of hidden impulses, especially in those episodes when Nona Gaprindashvili appears at international tournaments - ready for battle, very passionate and always fair. This feature is so striking and obvious that the director almost does not need to use additional details in interviews and dialogues (in which the chess queen’s character is well-revealed). In any dialogue, Nona Gaprindashvili is as open and expressive as possible in simplicity and immediacy in front of the lens. Even if she maintains a direct form of address and behavior in any lighting, in closed dark interiors, seeing and recording this feature is undoubtedly the merit of the film.

I found Nana Alexandria’s and Nana Ioseliani’s portraits, divided into biographical, emotional replicas, to be slightly less interesting. These characters are often seen in the relationship between the four, where some of them easily maintain their unwavering confidence to the end, like Nona Gaprindashvili, while others carry the most interesting, full of twists and turns episodes of their own biography and character with more question marks. This is just an opinion, an impression created about the artistic image, which the film leaves, and not reality itself. Another thing is that reality is a naturally acting subtext, a current. It is precisely something that creates the group and sharply expressed, individual portraits of this four.

In Nana Ioseliani’s gaze, in Maia Chiburdanidze’s strange smile and her interest in nature, in Nana Alexandria’s practical steps, the power of the past is felt, and in Nona Gaprindashvili’s calmness and dignity of the wisdom of the ages characteristic of chess seems to appear. It is enough to listen to the story told by Milunka Lazarević about how Nona Gaprindashvili made the decision to save her colleagues in wartime to understand the principle behind Gaprindashvili’s own simplicity and how unthinkable it is to discover a lie in the feeling of this depth.

The whole charm of documentary is in its narrative segment, in the form that creates a strange and authorial vision from reality through imagination. Perhaps not new, but on the contrary, fully understood and full of interest in events and people. This is not just a chronicle - a documentary is an individual example of attitude, artistic vision, but all this becomes even more complicated when we touch on important biographies. Either the integrity of the portrait emerges from them, or it does not.

Tatia Skhirtladze’s documentary is also a chronicle. It may be imperfect (perhaps the film crew did not even claim this) but, on the other hand, it is very important as historical material and as a unified image of a self-existing, naturally formed phenomenon. Why and how did it happen that chess champions did not let this title go from Georgia? The author is also interested in this, although this is a humanly understandable question for her, expressed in soft rhetoric, and nothing else, not a claim to explain what needs no explanation. Along with the analytical mind, this is the coincidence of the accumulated resources and energy that characterized that era. Along with the difficulties, frameworks, obligations, this is a process, both inexplicable and full of richness. What and how changes occurred after the champions’ era is another question, and Tatia Skhirtladze might be more interested not in this reality, but in the champions’ human, personal image through the prism of time.

Glory not only to the queen, but also to the dignity, which can be read in any short remark and look, but never changes, especially where documentary cinema can reveal its unerring knowledge.

Ketevan Trapaidze