Modern Georgian cinema often explores a person’s the inner loneliness, pain and invisible traumas. This tendency is especially noticeable among young directors. They boldly try to convey emotional topics with small budgets, through narratives based on personal stories.

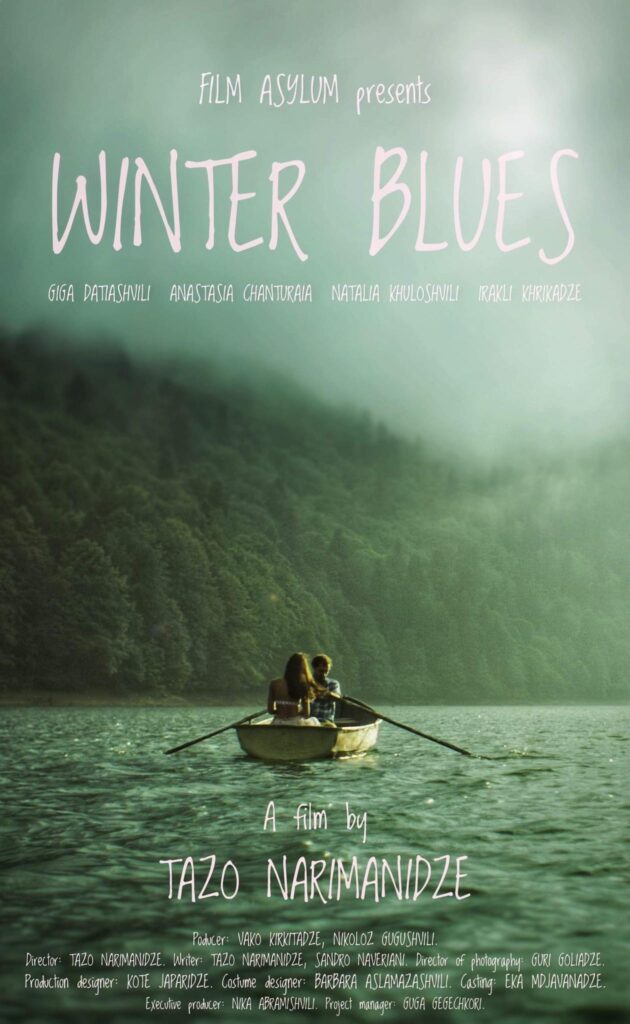

Tazo Narimanidze's film, “Winter Blues” (2021), belongs to this type. By focusing on psychological drama, it attempts to convey a modern person’s inner crisis on the screen. This is a film about loss, the breakdown of relationships, the struggle with oneself, and the fact that physical escape cannot heal the pain going on inside. The only solution lies in talking to each other.

At a glance, the film plot is quite simple: to overcome depression and a severe crisis in his marital relationship, the young writer Sandro leaves the city and goes to the village where he spent his childhood. This simple story of escape slowly turns into an internal drama.

The film begins in a darkened room. Sandro sits at the computer and works. Or more precisely, he tries to work. His wife, Anna lies speechless, almost motionless behind him, on the sofa. These first shots already accurately establish the emotional tone of the film: there are problems in the relationship.

Sandro's remark – “take off your shoes, or you’ll soil the sofa” – seems like an insignificant phrase, but in fact it is a symbol of the entire relationship. This is not just taking care of the sofa, it is an expression of irritation, fatigue and silent aggression towards each other. A small quarrel indicates from the very beginning that this couple has been living in the same space for a long time only physically, while they are already emotionally separated.

One of the important lines is formed by Sandro's psychotherapy sessions. The viewer learns that the main character is depressed, cannot find the strength to finish the novel and is closed in himself. The psychologist's advice to change places turns into a classic dramatic impulse: it seems that new space erases the old pain. Going to the village is unacceptable to Anna. This detail already makes it clear that the couple no longer has a common solution. Sandro's decision to go to the village alone is focused on individual survival, not on the relationship.

On the way, Sandro meets Sesili, a young girl who is also going to the village to spend the summer. Their acquaintance very quickly develops into emotional closeness: they watch a movie together, swim in the lake, take walks. In these episodes, the village is presented as a temporary place of freedom A space where Sandro seems to be starting life anew, although the awkwardness of this is felt right there.

The connection between Sandro and Sesili seems pure, light and free at first, but its moral problematic nature gradually becomes apparent. When Sandro's friend, Ioane arrives in the village and Sandro is forced to tell the girl the truth about his family situation, a real conflict is seen for the first time, which changes not only the relationship between the characters but also the attitude of the audience.

The moment when it becomes clear that Sesili knew about Sandro's wife from the beginning is particularly interesting. This detail presents her not as a victim but as a conscious participant, which adds more moral complexity to the film.

Towards the end, the main trauma emerges: Sandro and Anna had a dead child. It is this loss that becomes the main reason for the gradual breakdown of their relationship. They cannot forgive each other, they cannot find words to speak, and they are going through the same tragedy separately. This discovery completely changes the perspective of the film. What previously seemed like an ordinary family crisis turns into a story of mourning, unspeakable pain, and guilt. Anna takes a particularly radical position, unable to accept the trauma while Sandro tries to regain his will to live.

The film has a “happy ending:” Sandro returns to Anna, and Sesili continues her life away from them. Formally, this finale is a sign of reconciliation, a way out, and a new beginning, but it is here that one of the film’s main weaknesses appears - the dramatic gravity accumulated throughout the story, the depressive atmosphere, and the unfinished peace seemed to demand an open or more tragic ending. The happy ending partially disrupts the psychological logic that was being formed in the middle of the film. There is a feeling that the internal conflicts have been superficially resolved and unreally resolved.

One of the strongest formal elements of the film is the black-and-white, handheld episodes of childhood memories. The camera shake, rough texture, and monochrome imagery create the feeling that there was something sweet in the past that the main character does not want to forget. These sketches add depth to the film and bring the viewer closer to Sandro’s inner world. This is where the film becomes sincerest.

It is interesting to characterize all three characters separately, because each of them carries a different inner turmoil. Sandro is a person who is physically alive but internally frozen. He is a writer but he can no longer write; he plays the role of a husband but he can no longer understand his wife; his psychological state is completely enveloped in loss; The trauma of his deceased son is not only grief for Sandro but also a life burden that hinders his every action.

For Sandro, Sesili is not just a new love. She is the key to a new life. In this relationship, Sandro is not completely sincere - he lacks the strength to break with the past. It is precisely in this ambiguity, between his closeness to Sesili and his desire to return to Anna, that his main inner conflict is revealed. He is not a strong hero. He is a weaker, more unstable person who makes mistakes not out of evil intent, but out of spiritual weakness.

Anna is the quietest, but one of the strongest figures. Outwardly, she seems passive, often lying on the sofa, speaking little, rarely expressing emotion, although in reality her inner world is much more radical than that of Sandro. The tragedy of her deceased son is not only grief for Anna but also the destruction of the world, from which she no longer recognizes the existence of a way out. If Sandro tries to escape from the pain, Anna remains in pain. She does not look for a new space, does not look for other people, does not look for ways to survive, she seems to be punishing herself with constant confinement. Anna is especially harsh towards Sandro. She cannot forgive her husband not only for his actions but also for the fact that Sandro is trying to continue living when his life is over for her. This difference has finally broken up their relationship during the mourning process. Anna is a person who lives with trauma and no longer leaves room for reconciliation or movement. Her reconciliation with Sandro and pregnancy in the finale may appear ambiguous: on the one hand, this is a sign of the return of life, and on the other hand, the question remains whether Anna has really healed or simply come to terms with life.

Sesili is the brightest, lightest and strongest carrier of energy. She appears when Sandro needs new energy the most, and that is why all the scenes related to her are filled with peace, laughter, water, summer light. Sesili represents a world in which pain seems to exist. A very important detail is that she knows Sandro's family situation from the very beginning. He is not just a misguided young man and consciously agrees to a temporary relationship with a man who already has a family. That is why their relationship at first looks more like a free game than real love. Sesili neither tries to understand Sandro's real problems nor is she involved in his tragedy. She remains on the edge, as a temporary consolation.

Sesili's final disappearance is one of the most logical and symbolic decisions. She cannot remain in Sandro's life because her function was precisely to be a consolation. Sandro's real life is still connected with Anna, trauma, and responsibility.

The film seems to consciously avoid aestheticization. The village is not romanticized: a polluted lake, an unaesthetic environment, a simple interior - everything refuses visual beauty. The cinematography serves a documentary style more than poetic cinema. This approach is both the strength and weakness of the film. On the one hand, it creates a harsh honesty of reality; on the other hand, one often feels the emptiness caused by visual scarcity. The shots are shot in neutral tones, which in some episodes is emotionally exhausting. The use of colors strictly obeys the emotional mood of the film: cold, dark tones, gray and red color schemes constantly emphasize the inner pain. In the city scenes, everything that should have been corrected in the village is felt more sharply, although nature here also failed to become a source of peace. Color here is not an instrument of beauty, it conveys a psychological state.

Sound design and musical accompaniment are one of the most effective components of the film. The music appears in moderation and at the right moments, it does not try to forcefully intensify emotions, nor does it enhance the atmosphere more than necessary. Another serious disadvantage of the film is the dialogues. Many lines sound artificial and theatrical. The characters often do not speak as they would in real life, but seem to be repeating pre-written phrases. This is especially noticeable in emotionally heavy scenes, where the text does not reach the level that the situation requires.

Various secondary stories appear throughout the film but none of them are directly related to the main plot line. These details create a realistic background, as if life contains many small stories in parallel, although in some episodes these inserts violate the dramaturgical integrity of the film and distract attention from the main conflict.

Of particular importance is the fact that the director himself wrote the script, adapting it from a story. This gives the film an authorial touch, but at the same time, one can feel the difficulty of translating literature into cinema. Some dialogues and episodes seem more readable than watchable.

“Winter Blues” is a film about pain, loss and hope. About the fact that a person rebuilds his life, despite mistakes. The film remains an important attempt in the space of modern Georgian psychological drama, which leaves more questions than it gives final answers.

And yet, despite its flaws, “Winter Blues” remains an important event. It shows that big topics can be explored even with a small budget if the author is sincere. This work leaves you thinking, along with the questions that every person faces at least once in their life: is it possible to start a new life after a tragedy? And can a person escape a pain without running from himself?

Teona Vekua