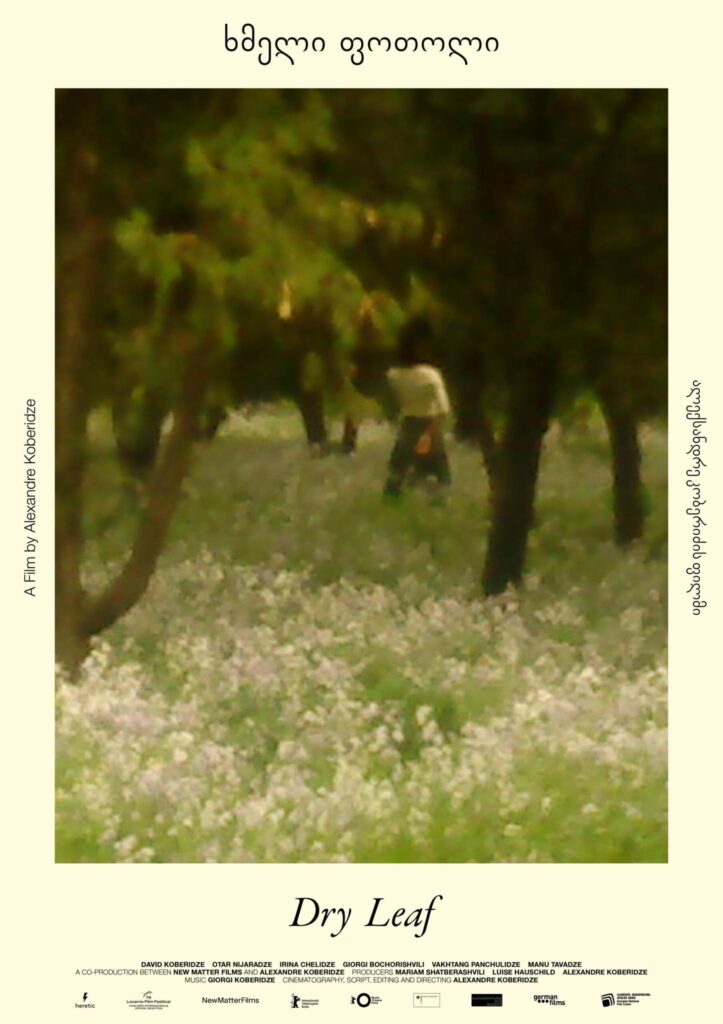

A Czech photographer Miroslav Tichý said: “If you want to take a real photograph, then you have to have a bad camera.” This phrase was the cornerstone of his creative philosophy, as he was known not only for his creativity but also for the camera he built his own hands from cardboard parts with. After watching Aleksandre Koberidze’s film “Dry Leaf” (2025), one really got the feeling that this director is influenced by the philosophy of the legendary Czech photographer.

This film was shown at the 26th Tbilisi International Film Festival. The cinema hall was full of viewers to see another masterpiece of Georgian cinema, which shows a 186-minute amazing journey through Western Georgia. The word “masterpiece” may sound loud but you realize that this assessment is as accurate as a bullet after watching the film.

The story describes the search for Lisa, a photographer for the magazine "Skhivi" (“Ray”). The girl's father, Irakli goes to find her after she does not return from a business trip. The main character tries to visit the stadiums that his daughter went to photograph, hoping to hear some information about her at one of the locations or meet the girl herself.

In the very first shots of the film, the director introduces us to interesting characters, those who are not seen but we can hear their voices. Such is Levan, Lisa's friend and colleague. He is also a journalist for "Skhivi," who accompanies the main character on this journey. Several such characters appear too. In the first part of the film, all this may be incomprehensible, but the reason for their disappearance becomes noticeable from the second half. Such people are only those who have not yet found themselves. That is why they are not seen. Levan has been working for the same low-circulation newspaper since his student days. It is also felt in his voice that he does not know what he wants to get from life. That's why he is physically vanished.

Another such character appears at the end of the film, the boy with the ball, whom Irakli talks to and asks about the location of the stadium, to which the boy replies that the stadium has been demolished and a hotel is being built in its place. This is the reason why it disappeared and is not seen. It is easy to guess that the boy might have "disappeared" after the demolition of the field because football was the essence of life for him. The boy with the ball is the only child in the film who "disappears," who did not lose his purpose but was made to lose it and this is revealed in a dialogue with the main character – if there is no stadium, where do you play football? – Irakli asks him, and the boy answers – everywhere.

In this journey, Irakli’s character is looking for the stadiums of the villages in Western Georgia, the places where Lisa was supposed to go to take photos but when he arrives at the place and interviews others, he learns that no one has seen her. Nonetheless, he does not give up, he continues his journey and along the way he finds places, people and animals that he falls in love with.

In “Dry Leaf” Aleksandre Koberidze’s Holy Trinity is revealed, which is the most important to him. These are: family, football and animals. The topic of family is the main theme of the film’s story but it is important that Irakli’s character is played by the director’s father, Davit Koberidze. The director himself is the cinematographer, and his brother, Giorgi Koberidze is the composer. In this project, it is clear that the family hearth was important to him when filming and that is exactly what happened. The father and son were actually traveling while filming and for this reason, the film is imbued with the aesthetics of documentary cinema. The viewer forgets about Lisa’s existence and changes color, like a “road movie” that explores the relationship between a father and his son. In the aesthetics of documentary cinema, in addition, the film is made of real locations and people who live in those villages. In many cases, the character’s conversation with them is real. This is a work of two categories – a fiction film that tells the story of a father who lost his daughter and a documentary film that depicts these places with sketches. All this is made even more magical by the quality of the camera, which evokes a nostalgic emotion in the viewer and this is due to the fact that the film was shot on a mobile phone.

In modern times, it is not surprising that films shot exist in this way, when modern smartphones allow you to shoot video of such quality that easily meet the standards set for a film. More recently, Danny Boyle was able to shoot his film, “28 Years Later” (2025) entirely on an iPhone 15 Pro Max, and technically it turned out great. The Georgian director didn’t find it interesting to work with a modern device that produces blurry, film-like footage that is comfortable during post-production. He needed to find a mobile camera that would simultaneously give him a nostalgic aesthetic and make the visuals completely untouchable during post-production. This is the reason why Koberidze shot the entire film on a 2008 Sony Ericsson V595 model phone, which turned out to be a late but amazing precedent in Georgian cinema. In this way, the director, gives great motivation intentionally or unintentionally to those new filmmakers who are unable to create a film for various reasons and consider that their project cannot be completed without expensive equipment.

“The single most important component of the camera is the twelve inches behind it” – these words of photographer Ansel Adams best describe Koberidze’s cinematography. He completely exhausted the capabilities of this low-quality camera and created high-class compositions that show us the soul and character of each village throughout the film.

The main issue in “Dry Leaf” becomes the process of movement and search along with the father’s quest for his daughter, so that he himself does not “disappear.” Consequently, this film may be a kind of antithesis to “The Taste of Cherry” (1997), one of Abbas Kiarostami’s iconic works. If the main character’s journey is depressing in the Iranian film, Irakli’s character is the main source of optimism for everyone in this case.

“Dry Leaf” is Aleksandre Koberidze’s deliberate artistic challenge to film industry standards, where technical minimalism creates aesthetic depth. The director consciously rejected modern high-definition cameras and used an old mobile phone, which provides a priceless analog, nostalgic tone in his vision. This uncomfortable visual was his way of reaching the real image that Miroslav Tichý was talking about. Low-quality, pixelated imagery blends with the documentary, “road movie” genre giving the villages of western Georgia a special intensity of authenticity and soul. The film’s aesthetics symbolically serve the story of how Irakli, together with his child, finds another ray of light for the leaf that has survived the withering.

Saba Makharashvili