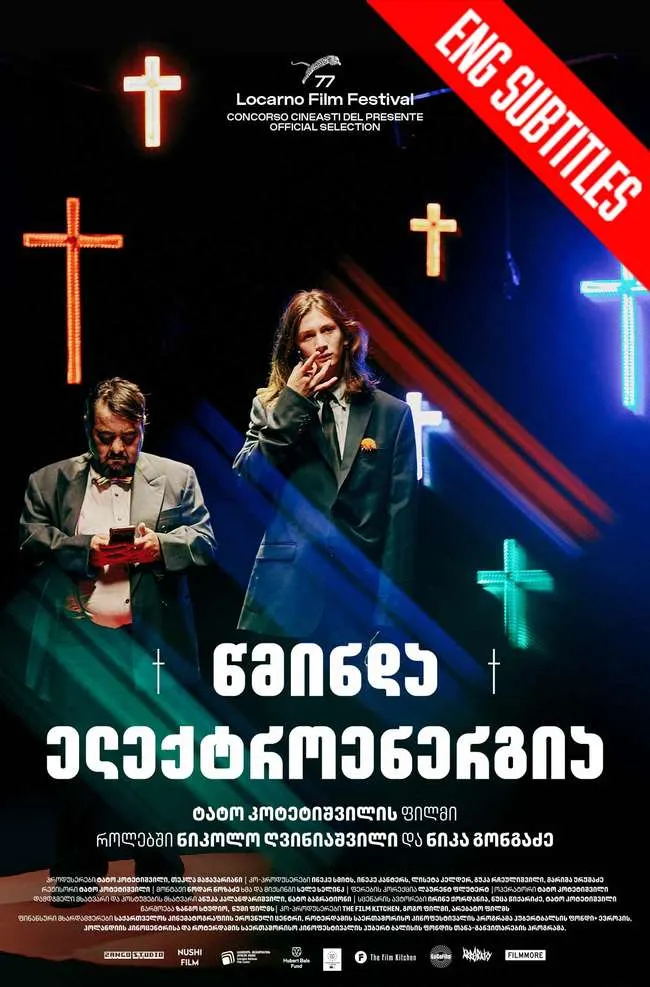

Tato Kotetishvili’s full-length film, “Holy Electricity” (2024), which is both a feature and a documentary creates a hybrid cinema. This is not an overly decorated, artificially sophisticated or scripted work. On the contrary, the director takes a very simple and seemingly everyday story, which is the reason why the film ultimately turns out to be natural and human.

It begins with the scene of Gonga’s father’s funeral. The camera calmly follows traditional Georgian customs without excessive drama. Here Kotetishvili’s main approach is visible – cinema does not mean surplus emotion, the main thing is people’s everyday life, movement and details that we usually do not pay attention to.

Afterwards, the action moves to a landfill, where a significant part of the film takes place. Two cousins, Bart and Gonga look for things here every day, sell, buy, try to survive. Bart is an adult, experienced and courageous man with problems and debts, while Gonga is a 16-year-old boy who is just starting out in life.

One day they find rusty crosses, and this discovery becomes the main line of the entire film. First, they make one cross, add colorful light and take to Gonga’s father's grave. At that moment, a man notices them and arouses interest in the young men. This is where their "business" begins. They add light to the crosses, restore them and then sell them door to door. In the film, this becomes the background for traveling around the city, meeting people, multiplying characters and deepening relationships.

The second part of the film becomes especially energetic when Bart loses money in a casino and temporarily separates from Gonga. Here the camera is divided into two lines, sometimes following one character, sometimes the other. This section is lively, funny, and full of energy. The relationship between Gonga and Bart is one of the warmest lines in the film. Bart plays the role of Gonga's older brother: he laughs, teaches, and feeds, while Gonga stands by him with his youthful sincerity.

Another of the warmest and most pleasant lines in the film is the short, tender relationship between Gonga and the gypsy girl. This relationship is special because it is completely free of unnecessary theatricality. Everything develops exactly as it might happen in real life with a teenager who is trying to interest someone for the first time, has to overcome his shyness and fight with himself for the first time.

From the very beginning, Gonga behaves very naturally next to the girl, silently watching, then looking away, trying to say something, it is this confusion and childish sincerity that gives the scenes their naturalness. Natural shyness creates situations that are funny, awkward and very sincere at the same time. This is not a romantic “history” for Gonga, this is the first experience of trying to get close to another person. It is true that their paths soon part, but it is so real until then, so pure that it somehow grows Gonga’s character. He seems to become bolder, more alive after this relationship. The gypsy girl appears in his life as a small but very important light. This is a completely simple but sincere relationship that becomes one small step on the path of a teenager’s growth.

A special role here is played by the fact that almost all parts of the film are made in a documentary style: non-professional actors, real locations, natural light, direct dialogues and a camera that seems to look life straight in the eye.

Casting unprofessional actors is associated with a great risk because often, in such cases, the resulting dialogues are shaky, and the actions are clumsy, but “Holy Electricity” is a complete opposite example. Here, it seems that the environment itself directs the characters’ behaviour. The actors move, talk, laugh, joke and are embarrassed so naturally that the film loses its sense of artistry at some points and becomes a documentary.

All this creates such atmosphere that you don’t notice where the script ends and real life begins. It seems to you that somewhere, in the Tbilisian suburbs right now, right next to us, there are exactly such guys walking around, collecting old things, accidentally finding crosses and knocking on your door to sell them to you.

“Holy Electricity” presents Tbilisi not as an ordinary setting, not as a city where the story takes place but as a living, diverse and cohesive space, where unexpected encounters are as important as the main storyline.

When Bart and Gonga go door to door with their neon crosses, the viewer seems to move with them through the neighborhoods of Tbilisi. This is where the main aspect of the city’s diversity begins, each person they knock on is completely different in their character, daily habits, questions and reactions.

At one door, they meet a woman who is crazy about animals, a little chaotic but full of human love. In another house, a group of feasters, noisy, quarrelsome, but open-hearted. Next, an elastic actress, who seems to be a character from the circus world. This is followed by a woman who loves aquariums, full of completely different questions and lifestyle. An elderly man in love with percussion instruments and two women full of virtues, who do not give up and perform daily physical exercises despite their old age.

This creates an important feeling that the diversity of people in Tbilisi is not a simple coincidence, but a wealth that the author views with great respect and openness. In Tbilisi, everyone is unique, everyone is a little strange, everyone is different, but it is precisely with these differences that they stand next to each other.

When Gonga and Bart meet these people, each encounter is not just a buyer-seller relationship for them, it is getting to know a part of this city, understanding its colors, characters, contrasts. Both characters grow along the way.

Life in Georgia may be difficult, chaotic, but it is precisely in this diversity, in this noisy city, in this undisguised real life that the most genuine love and friendship are born.

Kotetishvili’s camera never criticizes the characters. He observes them from afar, with detachment. With this approach, Tbilisi becomes real, full of amazing people whom you can meet at any time. The camera is often rough, not trying to capture the perfect shot or building a classic composition but it is still beautiful. Its “imperfections” are transformed into advantages. The viewer feels that this is life, not a staged scene.

The film music creates a real miracle. The fact that the musical material consists of six completely different modern works and several folklore fragments indicates the sonic depth. Modern electronic music is often a wordless expression of emotion – its bass, fast rhythms, give the film the energy of a modern city. At the same time, folkloric samples create a natural connection of Georgian culture with the characters. The dialogue between new and old music also develops one of the main topics of the film. Georgia is diverse. It simultaneously preserves the old and creates the new.

“Holy Electricity” is not only an interesting social observation but also one of the sincerest Georgian films of recent years. Tato Kotetishvili’s directing, screenwriting and cinematography work so organically fit together that the final result, a hybrid film becomes neither a pure documentary nor a classic feature but something in between, very interesting though. It reminds us that light is necessary for existence, when people work together, help each other, laugh, fall in love, suffer, it is from them that “holy electricity” is born, which turns the city, people and the audience into a single whole.

Teona Vekua