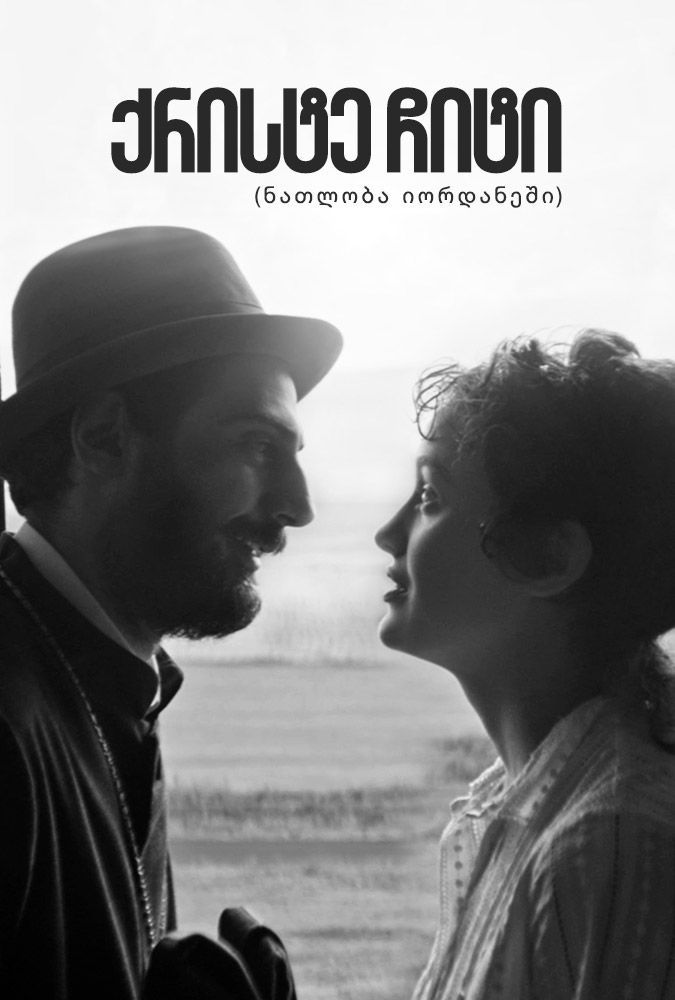

There is no doubt that acting and role-playing are thought of by humans but who fits whose role and which one they prefer is already dictated by their conscience. Most people might suddenly enter a role according to the situation, while some have only one mask adjusted and have it so tightly and firmly attached that it takes quite a long time to tear off this worn-out mask and face reality. Mikheil Kvirikadze’s feature film “Jesus Bird” (“Baptism in the Jordan”, 2021) tells us about this role-playing, about faith, about the outdated ideology from whose shackles we have not yet fully freed ourselves, and about many other things in general.

The main character of the film (Paata Inauri) is a crook gambler who escapes from the chasers and accidentally finds himself on a train, where he meets the little pioneers, accompanied by the pioneer leader, Ekaterine (Marisha Urushadze). They travel to the city to attend the Pioneer Union Olympiad. It is on the train that the story unfolds, developing an ironic, humorous and sarcastic narrative, which raises many questions, intrigues, and sometimes even confuses you until the end of the film, but, in the end, takes you on a small, interesting adventure in the original cinematic language.

The main character gives special preference to his nickname, pronounced with pride - "Churchill" (it seems that he is called by this name in the circle of crooks). He is "Churchill" to some and "priest" to others. Finally, the priest’s “mantle” is better able to disguise himself. The priest’s image appears several times in the film, not only visually, but also through the characters’ conversations. At the very beginning, we learn that one of the priests, while playing cards, sacrificed a cross in exchange for money, which was only a valuable item for him. Another priest, about whom the child tells the story, appears to be a disrespectful performer of his duty, since he tries to perform the rite of a child’s christening, who has come to his house in secret, with water washed from his own feet. And finally, the crook, the gambler “Churchill,” who undeservedly uses the priest’s anaphora.

The pioneers’ delight and awe when they discover that there is a “priest” in their compartment evokes particularly moving emotions. It seemed that not a priest but Christ Himself appeared before them in all His holiness. The pioneers, for whom the leader was considered the most sacred and praiseworthy being, now have the priest as their enlightener, inspiring reverence for Christ.

There is no irony in the film towards the Christian religion. It reveals how farce, fraud and all kinds of vice can be clothed in holy attributes. In this case, the best way is visual camouflage. The sight of a large cross and beard hanging around the hero’s neck inspires awe in the pioneers. If you are a crook, it will not be difficult for you to suddenly absorb the entire philosophy of the doctrine in a tailored robe and chirp like a bird in a preachy tone.

Despite the fact that the hero is a fraud, there is a protest against something, an inner rebellion in him. The director sarcastically mocks the pioneers’ red scarves in his image, which, according to “Churchill,” is a symbol of the uneducated crowd. A crowd that loses individualism and blocks dissent. The red color and specifically the scarf are the image of communism, which has been stigmatizing pioneers since childhood, turning them into puppets cut out of a single template, dishonored, enslaved, and obsessed with the dictator. It is interesting, why pioneers, a priest, and a crook? Or why does the main character mention Lenin, Marx, and Engels, and why does he call himself “Churchill?” The crook addresses the children with the words - “What do these Lenins-Marx-Engels teach? They teach us what kind of person a person should be.” And what does the current 21st century teach us? Democracy? Freedom of thought? How to maintain individuality, how to become an easily controlled crowd? By representing Soviet symbolism and reminding us of its political ideology, the director allows us to understand today’s assessment. It asks the question of why we have not been able to form a full-fledged democratic country for so long? Perhaps because we are still struggling with the remaining metastases that have not been completely eradicated in us.

Mikheil Kvirikadze reflects on the era of the 1980s but this does not mean that he is only analyzing the old times. Here he offers us an abstract understanding of time and place. Despite the fact that the “Iron Curtain” has long been “torn down,” the “Cold War” has become obsolete, the Soviet Union has collapsed and, as if from today's perspective, the pioneers are no longer the main characters, there are people who mourn the Soviet ideology, and not only people, but there is still a remnant of the Soviet mentality, false priesthood, hypocrisy.

The film is black and white, which is a mixture of old film aesthetics and, at the same time, modern narrative. The train symbolically embodies a time machine that travels through time and suddenly moves from a colorless, monotonous, “black and white” (formally red) closed space of the Soviet Union to an environment filled with hopeful, revolutionary pathos: the black and white shot, upon entering the tunnel, turns into color and children begin to sing “La Marseillaise.” As soon as they exit the tunnel (despite the fact that there is light at the end of the tunnel), the revolutionary pathos disappears somewhere and the film becomes black and white again. The train, as a metaphor for time travel, reflects the past and at the same time connects us to a hopeful present. It can see the image of yesterday’s past in the strokes of today.

There are many films where the plot unfolds on a train. Such are, for example, Temur Babluani’s “Flight of the Sparrows” and Giorgi Shengelaia’s “A Train Was Going By.” In both films we meet different types of people. There are also crooks and dreamers, but Mikheil Kvirikadze’s characters are completely different passengers, and his train is also completely different, as it represents a large empty space with a narrow corridor and empty compartments. From the window, fields, cattle grazing on pastures, hills and colorless, faded landscapes alternate. This cold visual aesthetic seems to paint us a model of a depraved world, devoid of all emotion, where lies and truth, hypocrisy and sincerity, faith and disbelief clash with each other, and everything valuable becomes worthless.

The pioneer mentality is overcome by Christian faith, which insidiously but in a different form intrudes into their lives. There is a sublime feeling that the christening rite is actually being performed and the pioneers are really being christened, not in a lake, but in the Jordan. The main character combines the images of Marx, Engels, Churchill, and a self-proclaimed priest. According to the hero, Christ also grew a beard, but he was not Marx. He himself has a beard, but he is neither Marx, nor Engels, nor Christ. Christ, according to the hero, is a bird that flew far away by its essence. He is a different bird, distinguished from other birds, but who is the hero of the film himself? Of course, a crook who suddenly becomes a “saint” in the eyes of others. When asked by the pioneers why Christ was crucified, the "priest" has no answer, he only has the "grace" to convert the infidel.

And finally, the question arises: does it really matter who christens you, a priest, a crook, or some passerby? The answer is sometimes yes, sometimes no. After all, all people are sinners, and even the priest is a person? Doesn't he have the right to love and be liked? Perhaps the main thing is that this mystery is "fulfilled," which gives rise to hope and faith that you have broken through some barrier and entered a new world. Even in the episode of "christening," you get the feeling that the character hidden in the anaphora of the priest is not a crook, but a good person who fulfills one of the great Christian mysteries and causes immense joy in the pioneers.

In the last episode of the film, for the pioneers, the image of the "priest" as their christianizing savior takes on an even more sacred appearance. The pioneers’s leader can see from the window how the “priest” thrown from the train by the chasers “flies away” and now the “Christ bird” who appeared as their savior, suddenly miraculously “flew away.” He flew away and left behind contradictory concepts, such as lies, arrogance, hypocrisy, and also purity, kindness, virtue.

This original film by Mikheil Kvirikadze, which is uniquely interesting for modern Georgian cinema, evokes very deep feelings and emotions, and can be discussed endlessly both from the point of view of visual aesthetics and its content.

Ketevan Ghonghadze