The name – Tato Kotetishvili – first was heard loudly in Georgian cinema in 1987, when then a young director made his first full-length feature film, “Anemia.” And the second time, it also happened loudly quite recently, in 2024, also in connection with the young director’s first full-length film, “Holy Electricity.” The second is the nephew of the first one, who made the film world, both in Georgia and around it (like his uncle in his time), talk about the new Georgian cinema and Georgia once again.

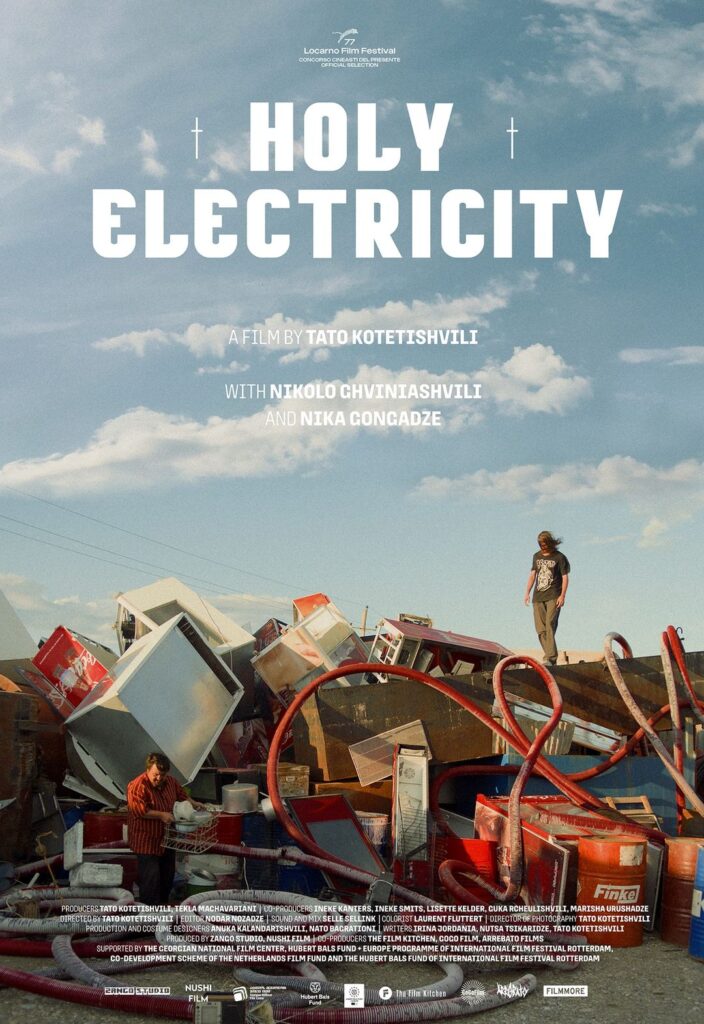

“Holy Electricity” is a co-production of Georgia and the Netherlands and is the winner of the 2024 Locarno International Film Festival’s “Golden Leopard,” a nominee for the Asia-Pacific Film Academy Award in the Best Director category.

Tato Kotetishvili’s style (as in the senior Tato Kotetishvili’s debut short films: “The Hero” and “The Train”) was “marked” in his previous short films – “Winter” and “Ogasavara” (winner of several international festivals, nominee for the “Tsinandali” award), and already then the peculiarities of his own thinking and vision were revealed.

“Holy Electricity” is about modern Georgia (just as “Anemia” was about the contemporary Georgia of that time), about the country people with different problems, different social beings, about people of different nationalities, ages, orientations, lives, and interests, who live in their real and on-screen reality created by the director himself.

The authors of the film’s script, along with Tato Kotetishvili (who is also the cinematographer), are Irine Zhordania and Nutsa Tsikaridze, and they have built the main plot and arranged and conducted a number of improvised episodes, characters, and passages. Improvisation and “picking up” characters and their stories is one of the main, instrumental foundations of the form and stylistic solution of the film. Such “fabrication” gives “Holy Electricity” special expressiveness and dynamics and speaks of the uniqueness of the director’s vision.

The film begins with death, with an episode of a funeral, burial, and burial ritual shot from the usual, yet strange, angle. When with the end of one life, someone else's life changes direction and a new one begins for two people – uncle and nephew – Bart (Bart Nikolo/Ghviniashvili) and Gonga (Nika Gongadze). A new life begins and the heroes' odyssey with new activities, new meetings, new acquaintances (among which Gonga and the gypsy girl's friendship stands out), new relationships, conflicts and non-conflicts, traveling from the dump, from the car "graveyard" to the city. Mainly, in the suburbs, at fairs, from street to street, from apartment to apartment... Following the father's debts, in a literal and metaphorical sense. And plus Bart's newly incurred debts.

The beginning of the main story is that after the father's death, the uncle promises his nephew that he will not abandon him and a new relationship begins in their lives, in search of means of existence. Then they find a “magic chest” – a box/suitcase of farm supplies or tools, full of old and unknown crosses (maybe those of graves or something else) and decide to equip them with neon lights and sell them. The idea works, and Bart and Gonga’s “small business” spreads out across different spaces of the city, often moving into the city’s hidden, unfamiliar, and sometimes publicly open and familiar spaces.

The odyssey that began at the dump passes through other spaces and, along with many places, also includes many stories. Each new place and new encounter, not in itself, but together, unfolds into a vast panorama. It eloquently combines social, private, personal, LGBT, identity and other ordinary and extraordinary issues about rejection, acceptance, love, compassion, solidarity, the usual "standard" lifestyle, choice, coercion, self-defense. About families with many children and few children, single and lonely people. About how people of different types, qualities, customs, nationalities, worldviews, different ages and psycho-emotional categories live in homes, streets, markets, in settlements, about what troubles them and what makes them happy, what and how is life, from their perspective and involvement.

There are many characters. The main, secondary and episodic roles are played by non-professional actors, and most of them “play” themselves, fragments, characteristic episodes from their own lives. Everyone speaks in their own language, lively, natural, without “censorship” and, of course, obscenely.

The film unfolds in several spaces. In rooms and streets filled with useless, old things, in families with similar things for sale piled up on the ground, around (which is often seen at fairs, Dry Bridge or other sites of street trading). In other spaces - ruins, abandoned buildings, garbage dumps, wrecked car, mountains of tires, steel barrels, refrigerators, broken things and discarded furniture, scrap metal, rusty and abandoned booths. This is another world, cries and messages from the past, when all these things and objects were effective, functional, but now they have become trash.

Tato Kotetishvili shows places and events from his own perspective and with a sense of meaning. He covers many places, neighbourhoods, corners, many objects and even enters places where no one would think of entering, or where an outsider, a stranger, might not even enter. And everything is surrounded by a lively rhythm, socially and publicly loaded crowded suburbs with vendors, intersections, subway entrances and platforms, street musicians, passing citizens who accidentally meet in the shot and even “stay.”

Bart and Gonga’s and everyone’s life together is like that of many people. With its relationships, connections, feedback, conflicts with each other and others around, the monotony and uniformity of everyday life and new lights – neon or sunlight rays, darkness, seclusion – isolation from oneself or the environment, inseparability from it, like colored pieces of smalt.

Tato Kotetishvili builds the structure of the film precisely on the principle of mosaic, in which some fragment of an incomplete form may turn out to be a real “fragment” of unequal size and shape, but organically embedded in a common plane or space. Like encounters with people of different types and categories in different places, accidentally caught in the camera lens and then precisely located, or this or that episode of different duration, which replace and continue each other with rapid and dynamic movement. Similarly mosaic, multi-thematic, and counterpointed is the music of Nodar Nozadze, Nika Paniashvili and Vako, which makes not, let's say, an emotional and falsely impressive effect but rather creates an atmosphere and its character, inner moods.

The director-cameraman and the main characters are involved in the course of life as if they were parts of it and with the opposite effect – the independent, self-contained flow of the lives of others, as if separated from them, organically passes into the Bart and Gonga, that is, into a fabricated story, into a fiction, which, despite its unity with the environment, has its own plot-ideological line, moves, "detours" and rules of dramaturgical development. Nodar Nozadze’s montage shows an internally charged and emotional, but still calm and balanced atmosphere, without any “extra” visual emotional enhancements, effects, “impressive” moves, radical leaps.

Many episodes are built on documentary material, however, these documents, which show different corners of life in different aspects and angles, are completely transformed into artistic and abstracted forms. Tato Kotetishvili takes documentary material, creates a document of the existence of a city, time, place, space, society and transforms it into an artistic fiction, an artistic reality through style, narrative manner and montage, peculiarities of description and imagination. Production designers Nato Bagrationi and Anuka Kalandarishvili select and create such interiors, exteriors and nature. Documentary transformed into artistry and artistic reality, is colored with humor, fun and sarcasm, joy and goodwill, without any “aggravating circumstances.” With sarcasm, which has become a rarity for Georgian cinema, which is still present here and there in the films of the new generation of directors. Cinema, which seems to be now regaining not only quality but also color.

These peculiar LED crosses, and not, let's say, ordinary crosses (as a kind of metaphor for today, which before being found and illuminated are thrown into the trash as useless things), have lost the meaning of a cult and an object of faith. Which, not only in its literal meaning and perspective but also in general, expresses the hypocrisy, spiritual emptiness and depreciated values of society. As in Otar Ioseliani's film, "And Then There Was Light," the characters, representatives of an African tribe sell tourists ritual idols as souvenirs after the invasion of civilization into the pristine and protected world.

Lela Ochiauri