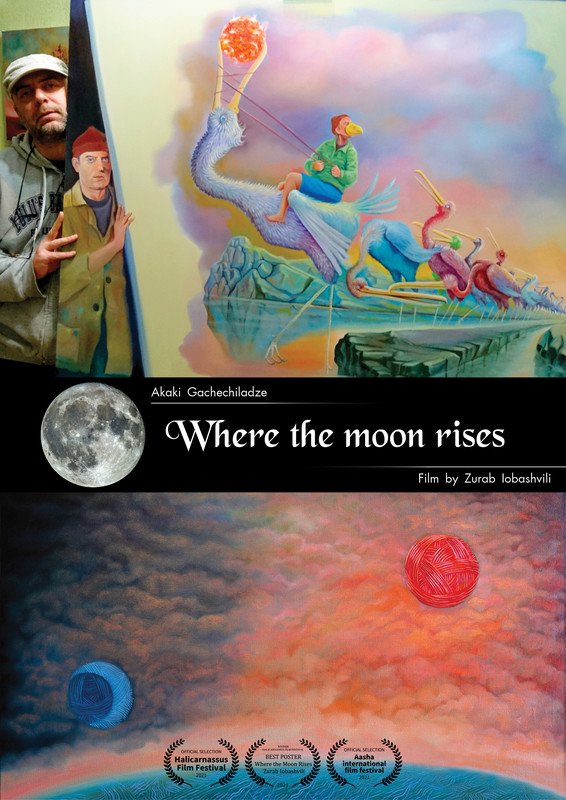

Zurab Iobashvili's short documentary film, "Where the Moon Rises" (2021) is a form of documentary television portrait and reportage, in which the main hero is not only an action figure, but also a narrator.

Television film has a great role in the history of Georgian cinema. Even now, offering new material to the audience often occurs according to these traditions, although the film, which should create a portrait, faces many challenges, providing Georgian documentary cinema technically and materially is difficult, just as it is difficult to find its original narrative form.

Akaki Gachechiladze’s portrait, of this extraordinary artist in itself, is interesting for the viewer in a diverse, literal sense, completely based on his "world."

Both the beginning and the end of the film, traditionally, seem like the beginning and the end of an easy narrative, but the persona itself, around which the narrative revolves, is already a separate space, with unusually good intentions and a human, direct perception of the world.

How can we turn a documentary portrait into a narrative about our own feelings and sensations? This is one of the most difficult tasks that every portrait documentarian has faced in the history of cinema. Neither the effects nor the terms of big funding can fully solve this dilemma if there is not a proper vision of the subject, the content of which the viewer should be interested in interpreting.

Such interest is caused by Akaki Gachechiladze’a nature, a dynamic portrait, very restless with his feelings. There are priorities in his attitudes, such as constantly thinking about something. There are also questions that the hero of the film shares with us with a childlike directness: from where and how does the moon rises, where are we in this huge matter, in the world, how is a feeling born, what is the driving force of artistic emotion...

This kind portrait speaking alive in front of us is very interesting, at the same time, it is very similar to the traditions of Georgian short film, which creates lively emotion, the best in its emotional expression. In the historical legacy of Georgian cinema the vivid portraits characteristic of documentary film were preserved at the time, and these films, with their lively characters, as if portraits created by actors, spoke very well of the ability of documentarians, above all, to create character before the eyes of the audience. What can a documentary portrait from the past and a new Georgian documentary portrait have in common? When Akaki Gachechiladze's sharp character traits come to the fore, we involuntarily recall the tradition of creating film portraits even in Georgian TV movies: stages of character recognition, initially at the easy first step, then in difficult dramatic episodes of life, then in a conflict situation...

In this case, the main character, the artist, can only be called a hero facing dramatic changes in the episode of the eye surgery, but the opening of his character also takes place in such a sequence and character changes: in front of us, in the cold of autumn or winter, a fussy but grave person is carrying some planks for the workshop, somewhere he goes, unhurriedly narrates what is familiar to him and understandable to us with hints. Nothing speaks of this existential reality more than the steps correctly interpreted by the director and cameramen and the figure of a man suspended on a stairwell. Akaki Gachechiladze, befitting an artist with a changeable character, is adequate in everything and, most importantly, he is an unusually open person, open to everything. Whatever his answer is, the truth is mixed with the portrait. With this, both the film and the Georgian cinema that created the portrait really win. However, there is one more but – this portrait, like many television portraits, has no implicit, implied layers of meaning. We are not saying that it is necessary to connect any story with any social or other event. It's just that, as a rule, such portraits represent an event that is set apart from the general trend. It is not the relationship with the mass that is important, but a better study of the world surrounding the main character, to perfect the portrait and not to know what environment surrounds the hero, with its detailed description.

Nevertheless, it should be noted that Akaki Gachechiladze's episodic, momentary relationship with people in the finale, in the middle of the film, during the operation, and the nature of his attitude towards the person who receives him, i.e. the author of the film, speaks of the feeling of the artist who is already clothed in this slightly lost opinion.

Instead of violence and negative emotions, that annoy the innocent and good creator, an ambition, which has really become so conspicuous and annoying in the modern world by painting, isn’t it better to depict by reviving and not with a bullet or other aggressive means? However, the truth mixed with a small replica becomes more expressive when the viewer involuntarily gazes at the graphic diagonal drawn in red. This is also a kind of optional artistic accent, which appeared a lot in the early examples of Georgian telefilms.

Akaki Gachechiladze's speech and his personality are divided into several main accents:

The first is that he, as a creator endowed with the gift of vision, is constantly and organically accompanied by the thought of the world existence around him. This thought is scattered in him, and the director identified it in all everyday situations, in the clinic, at the market, in the workshop, in the kitchen, wherever he appears, revolving around these immediate questions begin as well as the desire to fix the main mood in the hero's sad but kind look.

The second emphasis is related to the human feeling – not phobia, but the feeling in front of what is expected, and this feeling can best be identified in the helpless body ready for the procedure in the clinic, whose one eye drawn to the doctor is a living feeling about the artist's ability apart from the usual trivial emotion.

An interview, which should usually involve a lot of verbal material, is part of the emotion to be recognized between words and actions. Despite the dynamic lapses, this emotion is unified, but still the film's main flaw is a slight lack of artistic integrity, which seems characteristic for much of modern documentary portraiture. The search for reason can probably yield different answers, but one thing is what we are looking for and the other – what we get in return.

Georgian documentary cinema is always looking for a perfect character. This is a feature that has been practiced and tested for decades. Especially since the tradition of creating documentary material in the Georgian cinema of the 1960s allows us to think that this tradition should continue.

Akaki Gachechiladze’s narration, placed in an unnatural for him environment, in the service space (energy worker), also speaks of this versatility, and his business-like and responsible attitude even here, in a job that he probably does not love so much is a little funny, although he is interested and respects it. The director wants to maintain this versatility, but still has to rely completely on words and sound, which keeps us interested in documentary cinema, although it makes it less flexible in terms of narrative plasticity, the dominance of moving images.

In general, the existence of such portraits increases Georgian cinema from the viewpoint of documentary area, preserves the traditional and looks for new forms in portrait cinema, which is undeniably good. And it would also be good if the area of movement and imagination has a corresponding growth for Georgian documentary cinema, even for returning and preserving its genre diversity.

Ketevan Trapaidze