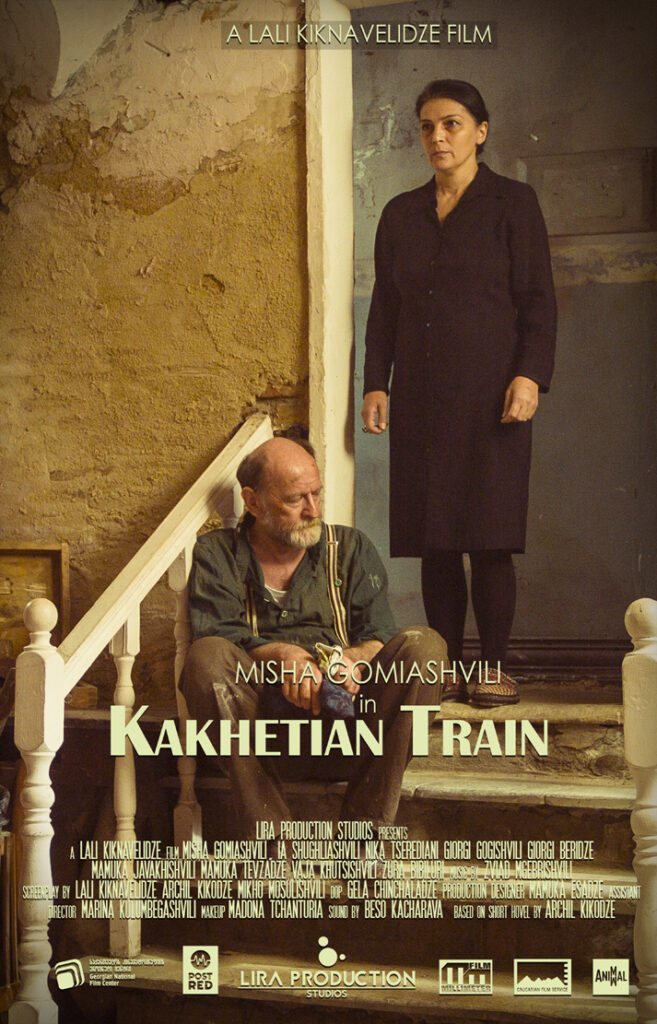

Different branches of art have their expressive means. Painting uses visual forms, literature uses words, and cinema uses both (and, of course, many more). It is interesting to observe how the same message, topic, is transferred from one field of art to another or how a work of one field becomes an inspiration for a work of another (and sometimes third) field of art. Such is Niko Pirosmani's painting, "Kakhetian Train," which first became the basis for Archil Kikodze's story of the same name, and then this story became a film directed by Lali Kiknavelidze (2019).

The film's disjointed storytelling style is embedded in the story itself. Misha (Gurgena in the story) who was thrown half-dead at the dump comes to his senses and sees a horse standing still over him. This is the horse that came from somewhere to the old part of Tbilisi and won the favor and sympathy of all the residents of the district, including Misha's young son. That is why this horse reminds him of his son.

The narrative takes place in three periods: when the beaten and tortured Misha somehow reaches home from the dump; chronologically earlier, when he is being interviewed by the police; and when he tries to understand and accept everything that happened to him, first of all, the murder of his son.

His son is not only a victim he is also a murderer of two people, a bandit, who was killed during an attack on someone else's family. Archil Kikodze's story mentions the topic of parent's responsibility for their child's behavior. The father has lost contact with his son, he understands, he can see what path he is taking, but he does not say anything to him, as if he is afraid of what he knows for sure, "he knew everything and did nothing to save his son or those people." This topic does not appear in the film. Misha (Mikheil Gomiashvili) loves his son very much and is angry because of his lifestyle, although only once does he utter words of reproach. He remembers his son's childhood, when he rushed to his parents' bed at dawn, and "the momentary, translucent and stormy happiness that came over him at the sound of small, bare feet rushing toward them."

Time has passed since then and the father first lost a common topic with his son, then the son himself, writes the author of the story. When he is beaten and cursed during the interrogation, Misha asks the policemen not to curse his son, he is dead, and in the film (unlike the story) he also says that he had a good son.

The film shows the father, who is shocked, and the mother, Ia (Ia Shugliashvili), who is saddened by the death of her son. The wife has found solace in the church and wants to take her husband there to ease the situation (it must be said that the wife's role is more defined in comparison with the story). She can see that the man is in a harder condition after the death of his son, the police took Misha to interrogation, where they tortured him to death and threw him in a garbage dump because they didn't think he was alive anymore. A man cannot forget this. They did not only torture him physically, but insulted, humiliated, mocked him, demanded that he tell where his son had hidden the stolen goods, which Misha knew nothing about.

Why the son became cold towards his parents, what he accused them of, what mistakes Misha and Ia made, this remains unknown to the viewer (as well as to the reader). However, it is a fact that this gap between them was cut by the son and despite his father's efforts, he does not accept his parents. He doesn't talk to them at all. People of different generations living in the same family cannot understand each other, as if they do not know each other. Moreover, the child is hostile towards the parents. The eternal topic – the conflict between generations seems to be an entity in this film. On the one hand, you sympathize with the main character, as a father whose child died and is an innocently tortured person, but you cannot share the pain that Misha felt due to the death of his son, who was a bandit, a thief and a murderer of people, who rejected his parents for reasons you do not understand.

The father is suffering. He could not tolerate with what he faced in the police and he could not tolerate with the death of his son, but the source of his pain is outside himself. He does not look within himself for answers. Nothing much would have changed in the story if Misha's son had been an innocent victim, and he had been subjected to brutal interrogation based on false suspicions. The topic of the guilty son’s death, relatively emphasized in the story, was lost in the film.

The narrative moves to a new level when Misha sees a copy of Pirosmani's painting at the marketplace. This is “Kakhetian Train." "A lion is not like a lion, and a bear is not like a bear" – until now it has been Pirosmani for him (and his circle). And now he felt something when he saw this picture.

In Archil Kikodze's story, the main character, a house-painter Gurgena, who accidentally overhears the a specialist’s conversation about Pirosmani's paintings while performing renovation work in the museum building, discovers a new world. Here, in these paintings, the birds, which, for example, surround the actress Margarita, mean love; in the work "Alazani Valley" happiness and misfortune are side by side; the whole world is in the background of "Crow, Rooster and Chicks;" the old man in "Yard sweeper" is both a yard sweeper and a saint at the same time... And again, Pirosmani continues the traditions of church painting but he does it in a modern way. That is why his works are like icons.

Pirosmani's painting, perfectly explained and appreciated in the story, should have been seen visually in the film. We ought to have seen that Misha understood something from these pictures, felt it. It was very complicated and it didn't work. In the story it is clear that the painting reminds the main character of happiness, but in the film he only says that it reminds him of his son and gives the painting to the priest. If you have read the story, you will remember that "Pirosmani's paintings are like icons" and you will understand why Misha brought a copy of "Kakhetian Train" to the church, and if you haven't read it, you won't understand it from the film.

If in the story the inner world of the main character was shaken by directly seeing Pirosmani's original works, in the film it started with a cheap copy of the artist and a photo printed on a calendar and sounded less convincing. The man was most affected by the fact that in this painting the train has tracks in front, but not in the back. The train with lighted windows seems to be coming from nowhere, it has no past, it goes forward and cannot go back. The past and the present are also confused in his head. It is true that in the film it is not clear why Misha was affected by this painting of Pirosmani but we can see that after that Misha, a craftsman, became an artist. He buys paints, brushes and locked in his studio begins to paint ecstatically. An inexperienced amateur will paint his pain due to lost happiness. In the picture of the story hero, Gurgena, there is a horse with a slightly big head, astraddle in the center, a sickle moon in the sky, and two small figures are visible behind – one is scared, his hands are raised, and the other, in a red coat, is aiming a gun. We can understand that it is his son, and the robber is surrounded by birds, a symbol of love.

The main thing in the film is the illuminated train, which has tracks both in front and behind. Here, in the background, we can see a horse that reminds the main character of his son and that came to the half-dead on the dump. On this horse sits Misha's son of the age when he used to run to his parents' bed in the early morning dragging his little feet. The son who was the age before his death, is also here – he aims a gun at a man with hands up (as in Pirosmani’s another work "Alazani Valley"). The content of the picture drawn by the main character was better decided by the authors of the film. Both the horse and the train are well combined in this picture. Painting this picture gave catharsis to the spiritually destroyed hero, the black-and-yellow glow of Pirosmani's "Kakhetian Train" was able to do what the church managed to do for his wife – consolation.

Ketevan Pataraia