On a calm and peaceful spring morning, when nothing disturbs the comfort and a new bright day begins, the old peasant with a deep-wrinkled face, along with his grand-daughter in an old boat will approach the uninhabited small island in the river bed – the "no man's land." Upon coming ashore, the man tastes the soil, stirs it with his fingers and finds a mouthpiece buried in the mud. It is left by someone. Along with the household items, the girl brings a rag doll and places it with her other personal belongings.

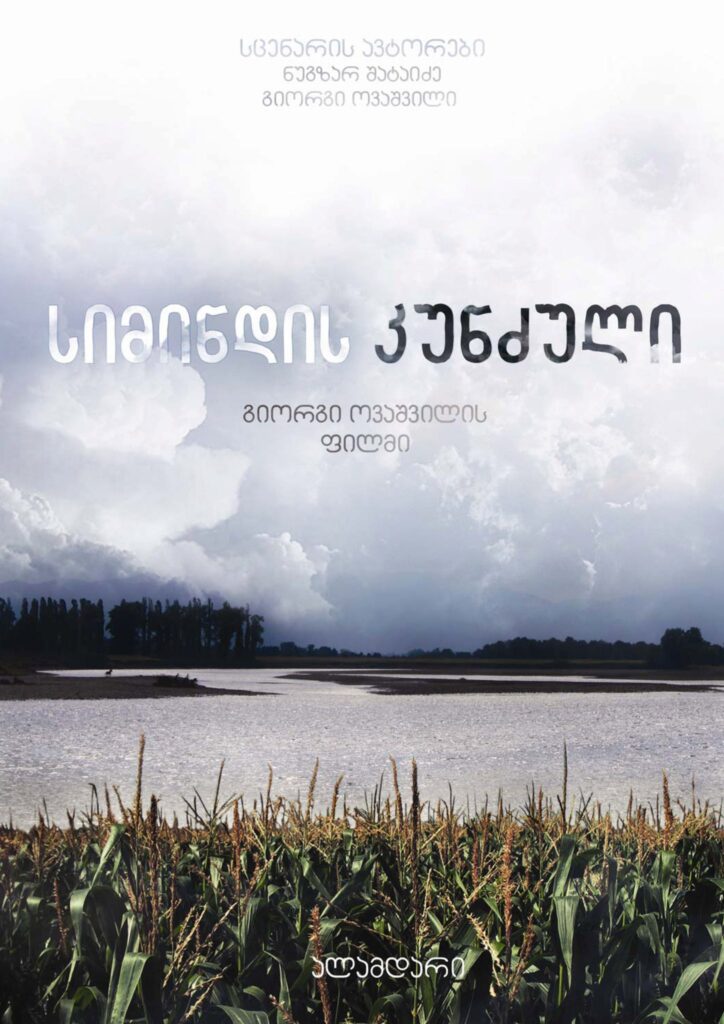

This is how Giorgi Ovashvili's second film of "Abkhaz Trilogy" "Corn Island" begins (2014, co-production of Georgia, France, Germany, Czech Republic, Hungary and Kazakhstan). The story takes place during the war in Abkhazia. More precisely, before its start and in the first months, on the Enguri River, on the "seasonal," fragile but nutritious island, which is “no man’s land” formed by the soil, silt and peat brought from the Caucasus in the spring along the flooded water.

Grandfather and grand-daughter are Abkhazians, their sheltered fighter is Georgian. Along the island on the both sides, the boats of Georgian and Abkhaz warriors are sailing in turns. Their boats do not intersect anywhere in this space.

The old man and the girl start building a hut out of planks and build it slowly. They sow corn. They take care tirelessly. Monotonously. Without a word. It is a ritual of dynamic work. Actually, with all stages. From the beginning to end.

It is they – grandfather and grand-daughter who create this time, this new world. They revive, but they don't make it sound. There is silence on the island. Only the sounds of nature – water, birds and leaves – are heard from a close distance and from somewhere far away, deaf noises coming from an invisible space. Time seems to have stopped now. It passes slowly and monotonously. The corn field is growing gradually. The field, as new (even short-lived) and ever-moving, is a metaphor for changing life.

There is almost no dialogue in the film. Only brief and necessary retorts are scattered here and there (in Georgian, Abkhazian, Russian). Only an inner hidden mood, a wordless but meaningful and emotional look, and also a wordless, silent and restrained action. No words are needed. Silence speaks volumes.

Big, long pauses and "stretched” shots devoid of some special content and effects which are at the same time telling and expressive. A monotonous silent landscape, a sense of the immensity of space and a generalized look of the real world, which is filled with the natural light of light sources – lanterns of day and night. And the audience, tensed and full of anticipation, looking at this cozy and calm landscape, which would be peaceful if not for the war going on somewhere nearby. But war is war and it is impossible to think about peace during its course.

The island is on the border, which seems to separate or connect two dimensions and also confirms the existence of a harmonious relationship, inseparability between man and nature. Even when the world begins to collapse, disintegrate, annihilate. The ongoing changes in people and the relationships between them acquire a physical expression, become generalized news – for any society in times of war and peace, past and present, surrounded by violence and enmity. Not just "here and now" but everywhere on earth.

The island separates and unites everyone – the people who live on it, who wander around (and break the rule against rudely intruding on someone else's world). On the one hand, Enguri – a natural element of water – seems to separate and connect Georgia with Abkhazia, a part of it, torn apart like an island. It is a border, a dividing line and a river of life that can be crossed if fate and people will. A trial from which those who have been washed must come out.

Nature fights man and man fights nature. At the same time, both give birth to a new life and cannot exist without each other. Nature creates an island for man and takes it away after he uses nature's creation. And if a man perishes with the island, as sacrifice in the water is sometimes necessary, life still goes on. Nature again gives him a gift – a new land in the water space, and man receives a gift as an heir, who gets a rag doll buried in the mud and saved from his predecessor.

The girl lost this rag doll just when her grandfather put her in a boat and immediately left the already almost sunken island in order to save her from the rushing water, where he himself sank along with the corn field. Together with the land that he brought to life, cultivated and awakened.

Where is this boat going – to save life or to perish? Will it survive the waves of the overflowing river, reach the shore or will it disappear? But no matter what happens, one thing is inevitable – someone will come again and sow corn again, tend the field again because nothing affects the eternal cycle of life – nature, the existence of land and water – neither war, nor death, nor separation – everything is transient, everything it happened and will happen, only life is eternal. This is the law of myth.

Then, when the world is covered with water and turbid and violent waves begin to cover the island, the land that has just blossomed disappears, when nothing can stop the disaster, the story takes the form of a peculiar and modern allegory of the flood. And it is transferred to the category of parable.

And like any fable, neither corn island nor the story unfolding on it or around it has any definite time or geographical boundaries. It goes beyond a particular circle and is imagined as a micro-model of the world surrounded by water that gives birth, creates, protects, purifies and even kills.

But nature, as always, has its own laws. Even people have their own laws – moral and ethical – which they do not violate even in the most extreme conditions, when facing personal danger or against their attitudes towards events.

Of course, corn island is not the Promised Land. Neither is it heaven. Not even a safe shelter. But there is a little bit of everything and it is a sign that someone settles there with hope and faith. He feels calm and safe until the war shakes his comfort again. And so it will continue as long as war and violence remain a part of life.

Just like Giorgi Ovashvili's first film of Abkhazia trilogy, "The Other Shore," as its final caption directly declares, is dedicated to his (our) homeland. Those who have been ready to listen and engage in dialogue for a long time and those who do not accept this dedication and do not share the director's position. It is dedicated to those who accurately assess the events and who see and appreciate them only from one shore, from one side, who cannot see anything around, except for one route and for whom Abkhazia, people, kindness, forgiveness and pardon are empty and meaningless words. And also those for whom there is nothing more precious and important than concepts.

Lela Ochiauri